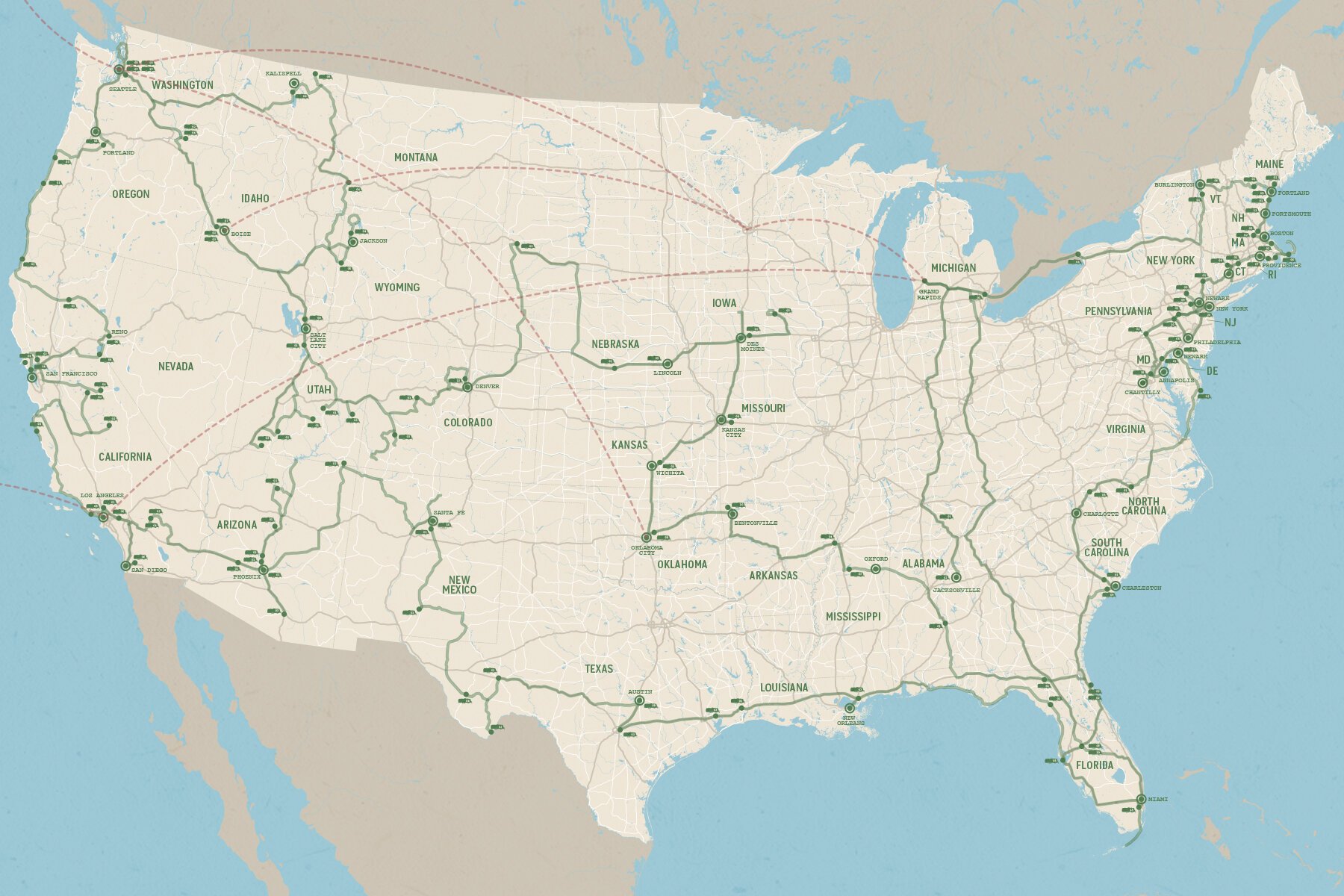

38/50: Alabama

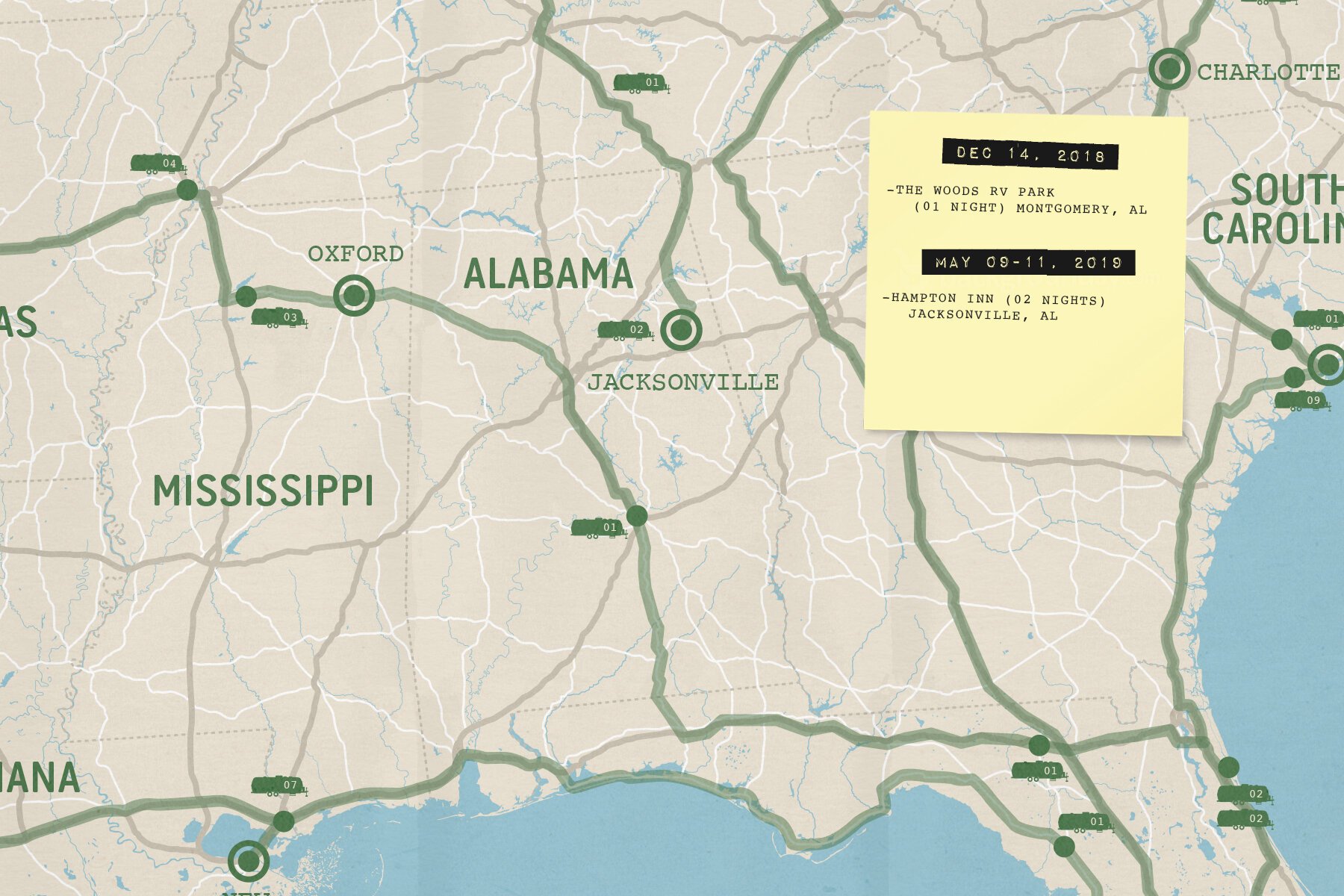

In December 2018, after we finished our STATE 36: MISSISSIPPI project in Oxford, we were on our back to Florida to spend our Christmas with family before resuming the tour after the New Year. On our way to Florida, we made a point to visit Montgomery, Alabama. Montgomery is home to a significant piece of our country’s history, and since much of the 50 States tour has come to include a real-life history lessons we learn along the way, this was another heavy hit of our dark past.

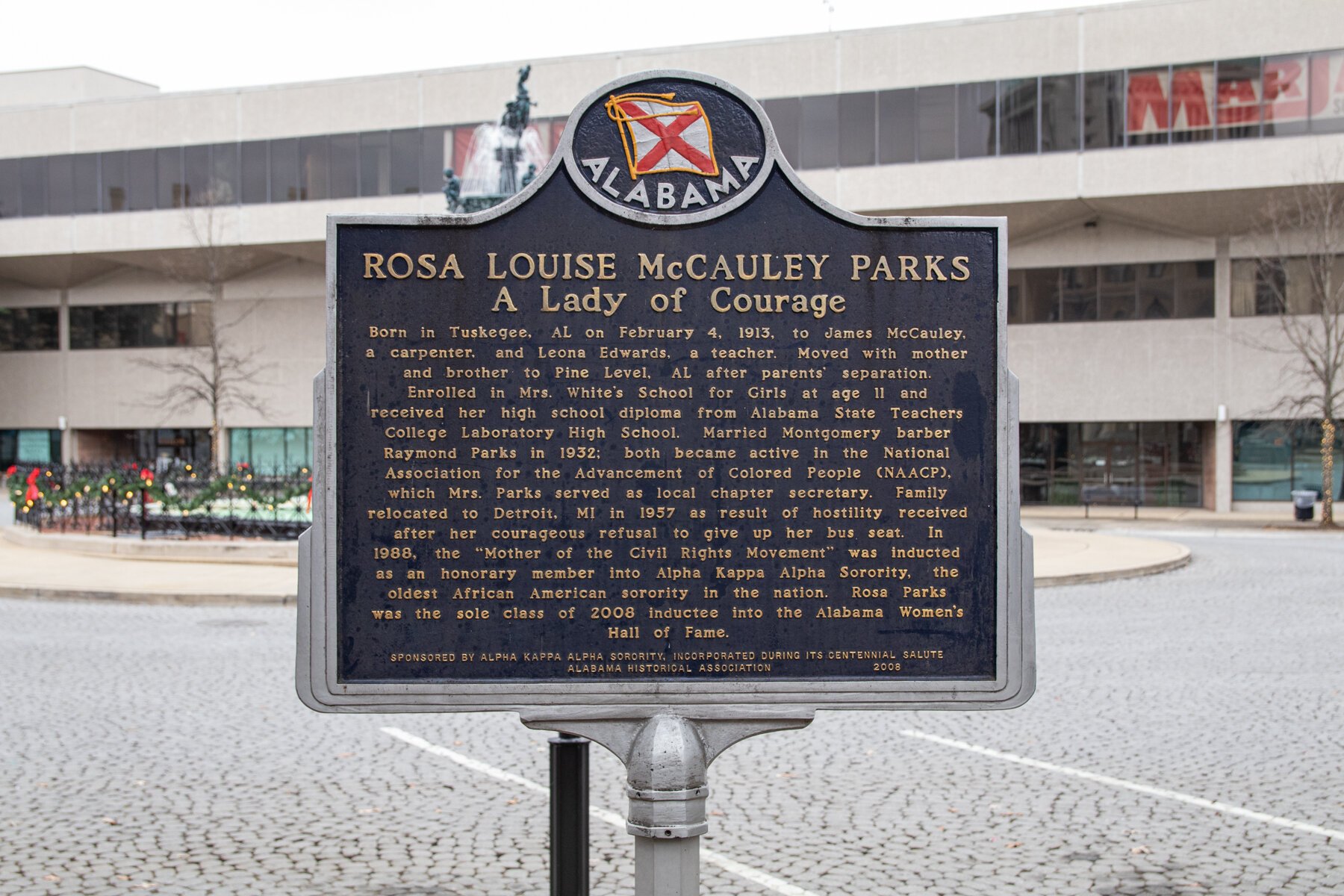

When we visited Mississippi, we made a quick detour to Memphis, Tennessee, to visit the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel where on April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated the night after he gave his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” address. Less than 350 miles from where Dr. King gave his final speech, he pastored the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery from 1954-1960. In 1956, Rosa Parks was arrested for not giving up her seat on the bus in Montgomery. In 1961, Freedom Riders were attacked by angry white supremacist mobs throughout Alabama in Anniston, Birmingham, and Montgomery. In 1965, after marchers were met with violence in Selma, Alabama on “Bloody Sunday,” their march from Selma to Montgomery was completed a few weeks later marked with Dr. King’s “How Long, Not Long” speech given on the steps of the state Capitol just up the road.

But long before these civil rights events were beginning to change and challenge America, these streets and rivers were used to transport, display, and sell men, women, and children into slavery.

Along this route, slaves were marched to the markets they’d be sold at. At this bus stop, Rosa Parks sparked a boycott and a movement where her Bible remains open to one of her favorite verses from the book of Proverbs. And, at the end of the road sits the Capitol building where Dr. King proclaimed:

“…It is not an accident that one of the great marches of American history should terminate in Montgomery, Alabama. Just ten years ago, in this very city, a new philosophy was born of the Negro struggle. Montgomery was the first city in the South in which the entire Negro community united and squarely faced its age-old oppressors. Out of this struggle, more than bus desegregation was won; a new idea, more powerful than guns or clubs was born. Negroes took it and carried it across the South in epic battles that electrified the nation and the world.

”

Continuing our Civil Rights Trail throughout Montgomery, we spent a considerable amount of time inside The Legacy Museum of the Equal Justice Initiative that transformed these buildings that sit one block away from one of the most prominent slave auction spaces in the country and mere steps away from an Alabama dock and rail station where tens of thousands of black people were trafficked throughout the 19th century. Without being able to take pictures inside the museum, it’s difficult to put into words the experience and the feelings that this 11,000-square-foot exhibit about the enslavement, terror lynchings, legalized segregation, and racial hierarchy in America evoked in me as a white male born and raised in the Midwest.

The museum not only powerfully shares the early history of racial inequality through engaging visuals, but they bring it into perspective on how that has created vast branches of contemporary issues, especially those of systematic racism, mass incarceration, and police violence — which is still all too real in America today. Many of their exhibits come from their in-depth reports and analysis, including: Slavery in America: The Montgomery Slave Trade report, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, Segregation in America, and those are just a few from their Racial Justice pillar. Their other two pillars of advocacy include Criminal Justice Reform and Public Education, both of which deserve your time to review and donate to support their continued efforts in healing our nation’s greatest wounds.

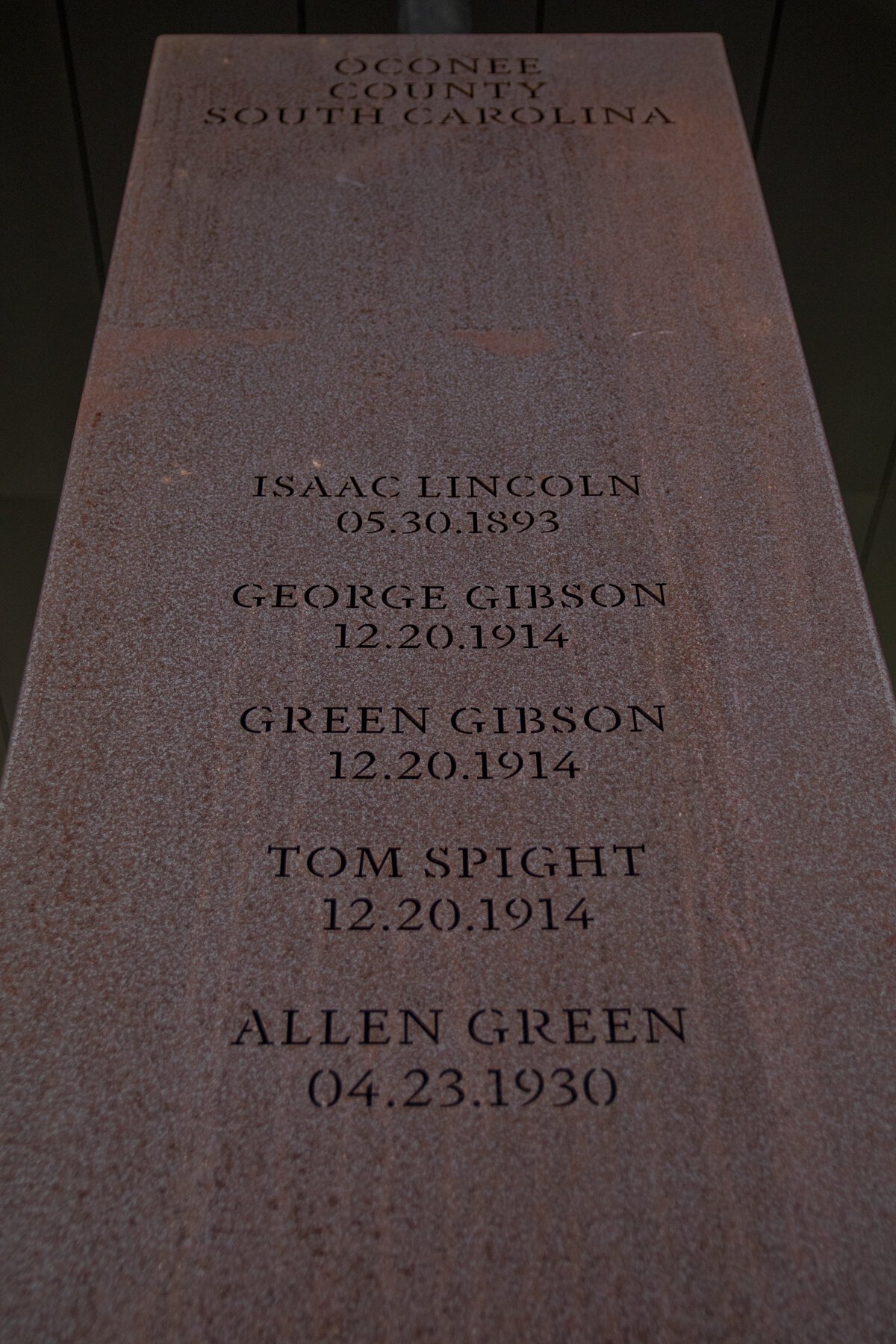

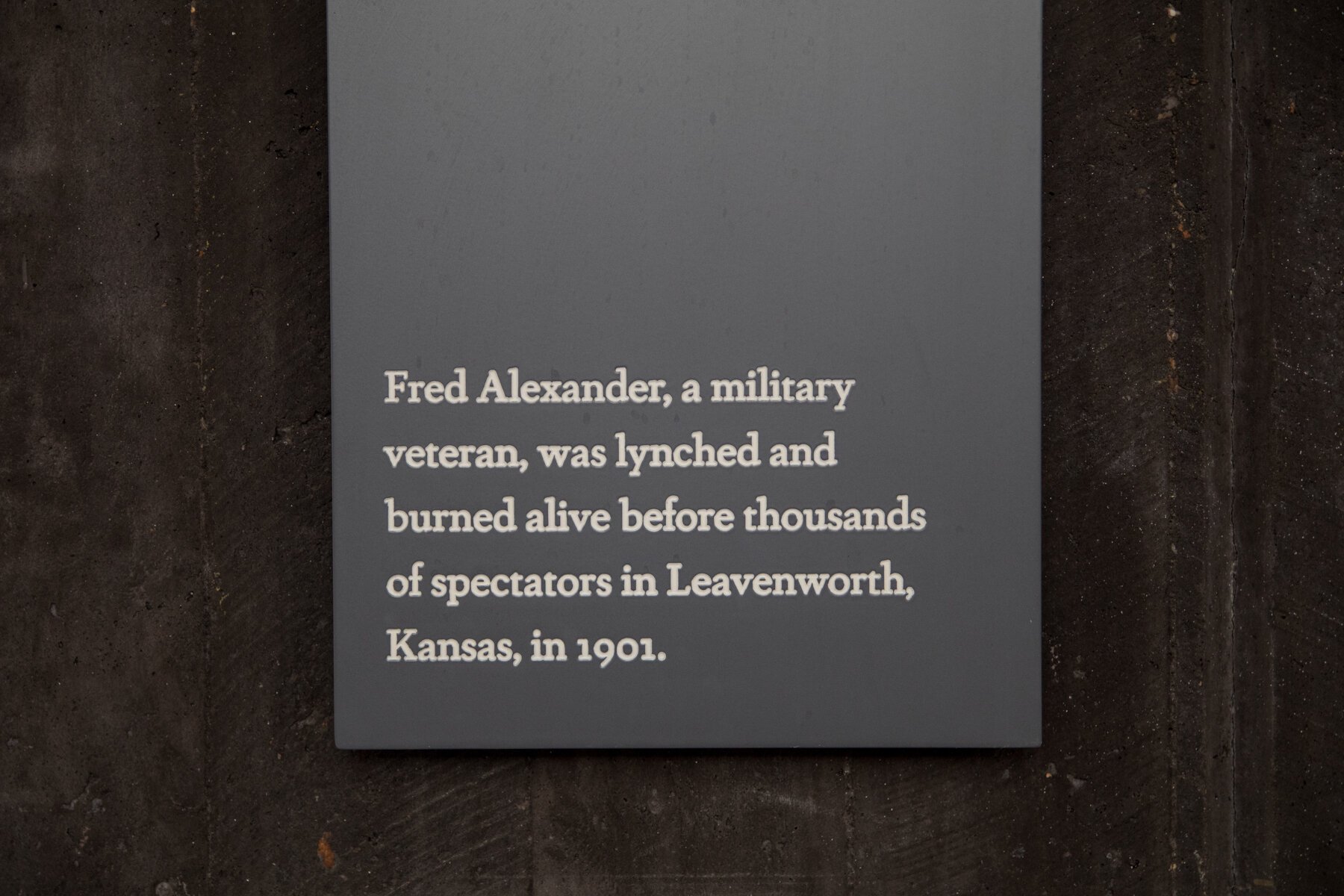

This memorial is a tangible result of research started in 2010 by the Equal Justice Initiative investigating thousands of racial terror lynchings in the South, many of which had not been documented. Their report “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror” released in 2015 uncovered 4,084 racial terror lynchings in twelve Southern States between 1877-1950, about 800 more than previously reported or publically known. They also documented more than 300 terror lynchings in other states, including Illinois, Ohio, and other non-Southern states during this time period.

“General Lee, a black man, was lynched by a white mob in 1904 for merely knocking on the door of a white woman’s house in Reevesville, South Carolina.”

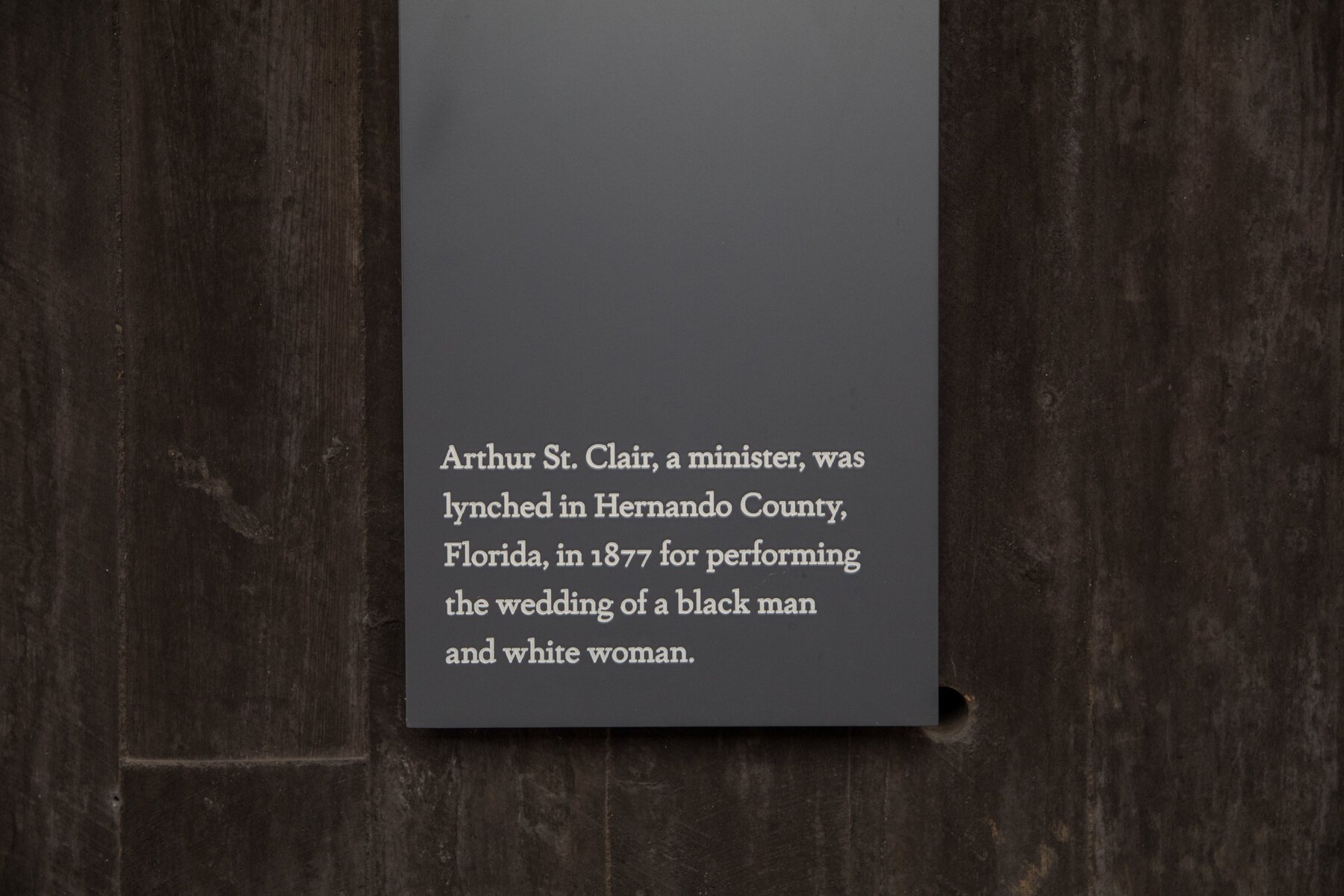

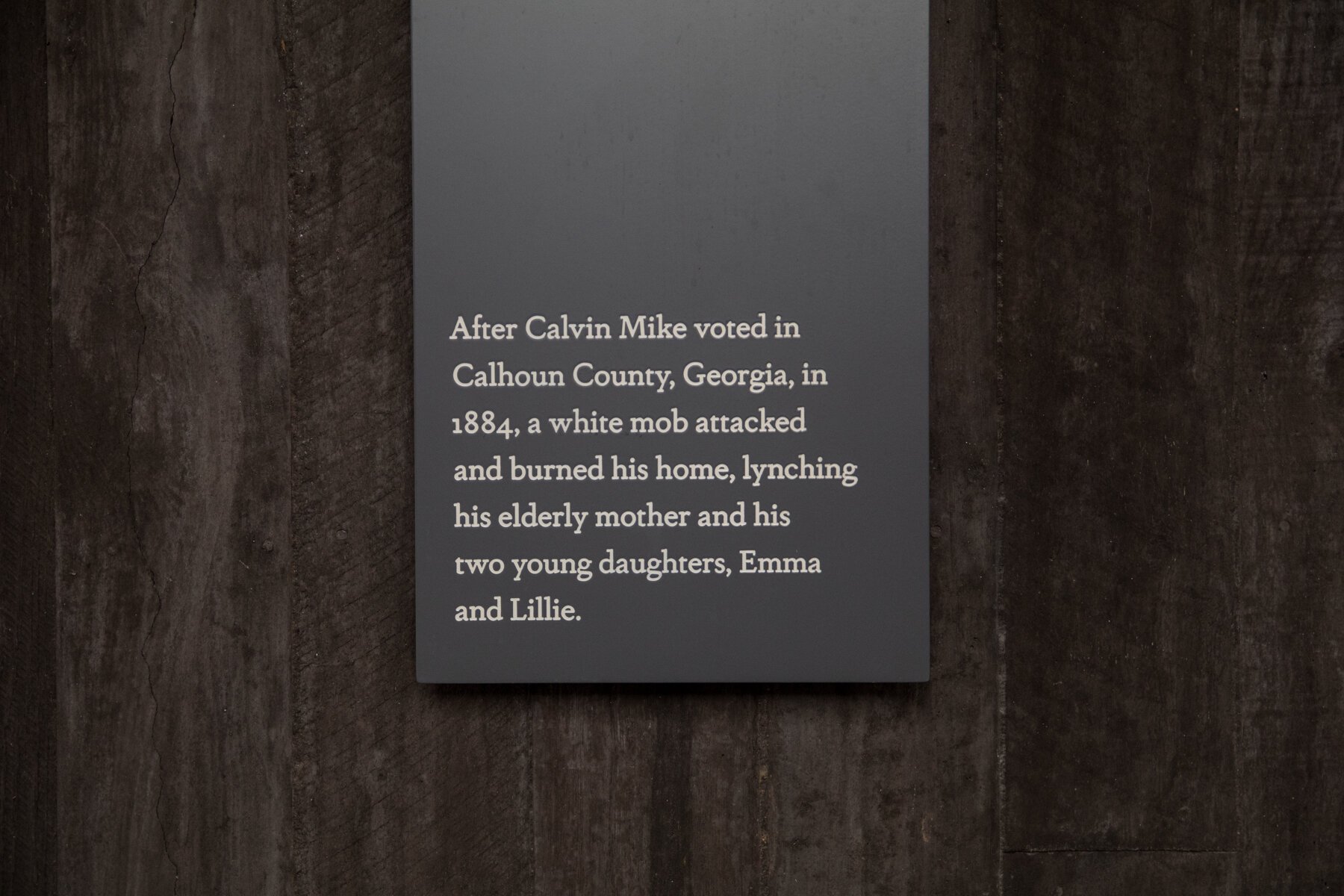

Among their countless devastating findings, they concluded that terror lynching was a tool used to enforce Jim Crow laws and racial segregation — a tactic for maintaining racial control by victimizing the entire African American community, not merely punishment of a crime but for “minor social transgressions.”

“White men lynched Jeff Brown in 1916 in Cedarbluff, Mississippi, for accidentally bumping into a white girl as he ran to catch a train.”

Unfortunately, those are just a few gut-wrenching examples from their in-depth research. Worse yet, the white perpetrators of these terror lynchings and horrific acts of violence were never held accountable — many of these public spectacle lynchings were attended by the entire white community and were being conducted as celebratory acts of racial control and domination.

“In 1918, Private Charles Lewis was lynched in Hickman, Kentucky, after he refused to empty his pockets while wearing his Army uniform.”

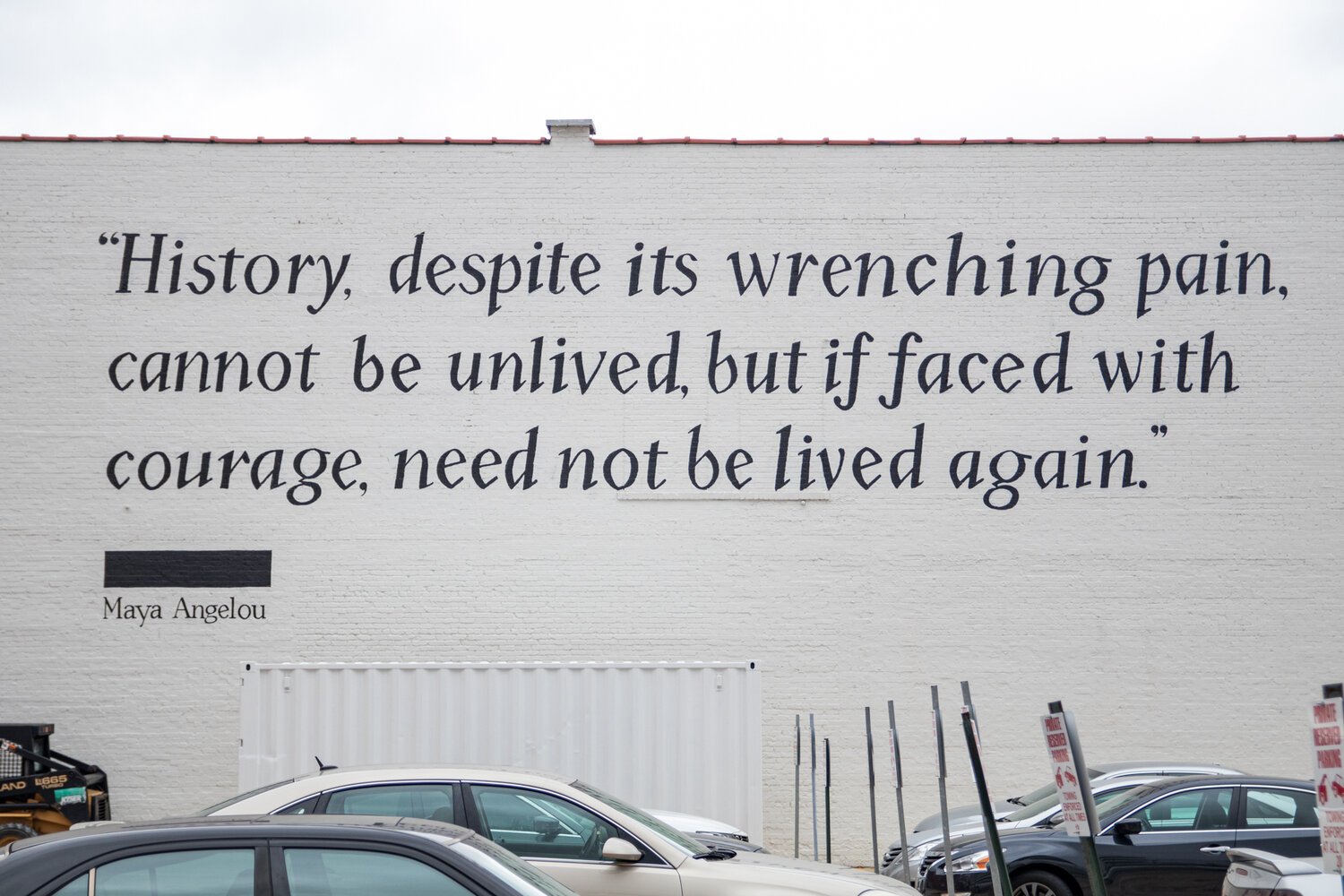

If you still don’t think we have a racial problem in America today, please consider these happened only one or two generations ago. This isn’t ancient history. This is America’s history, and it’s on us to face it head on in order to do something about it.

“In 1940, Jesse Thornton was lynched in Luverne, Alabama, for referring to a white police officer by his name without the title of mister.”

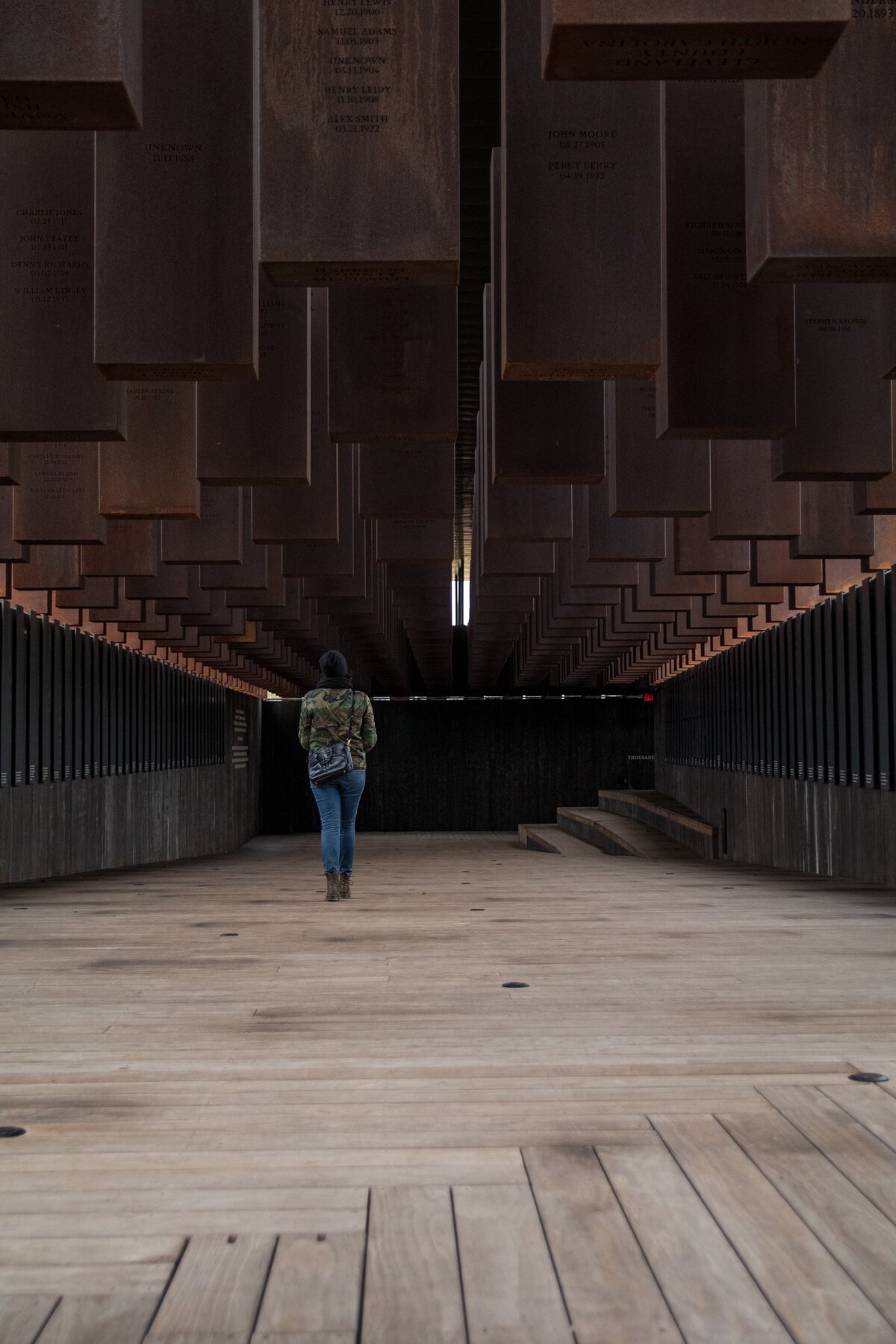

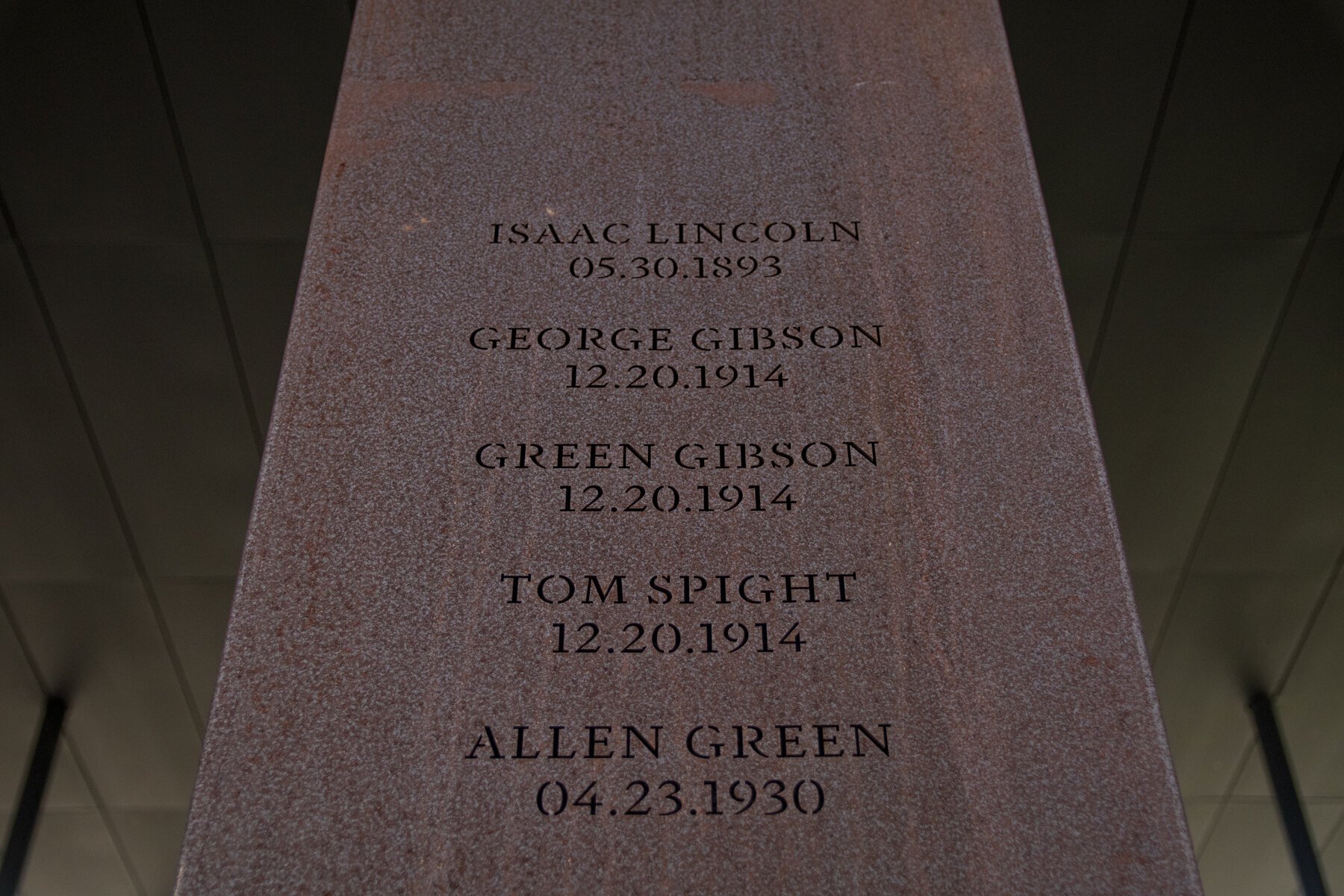

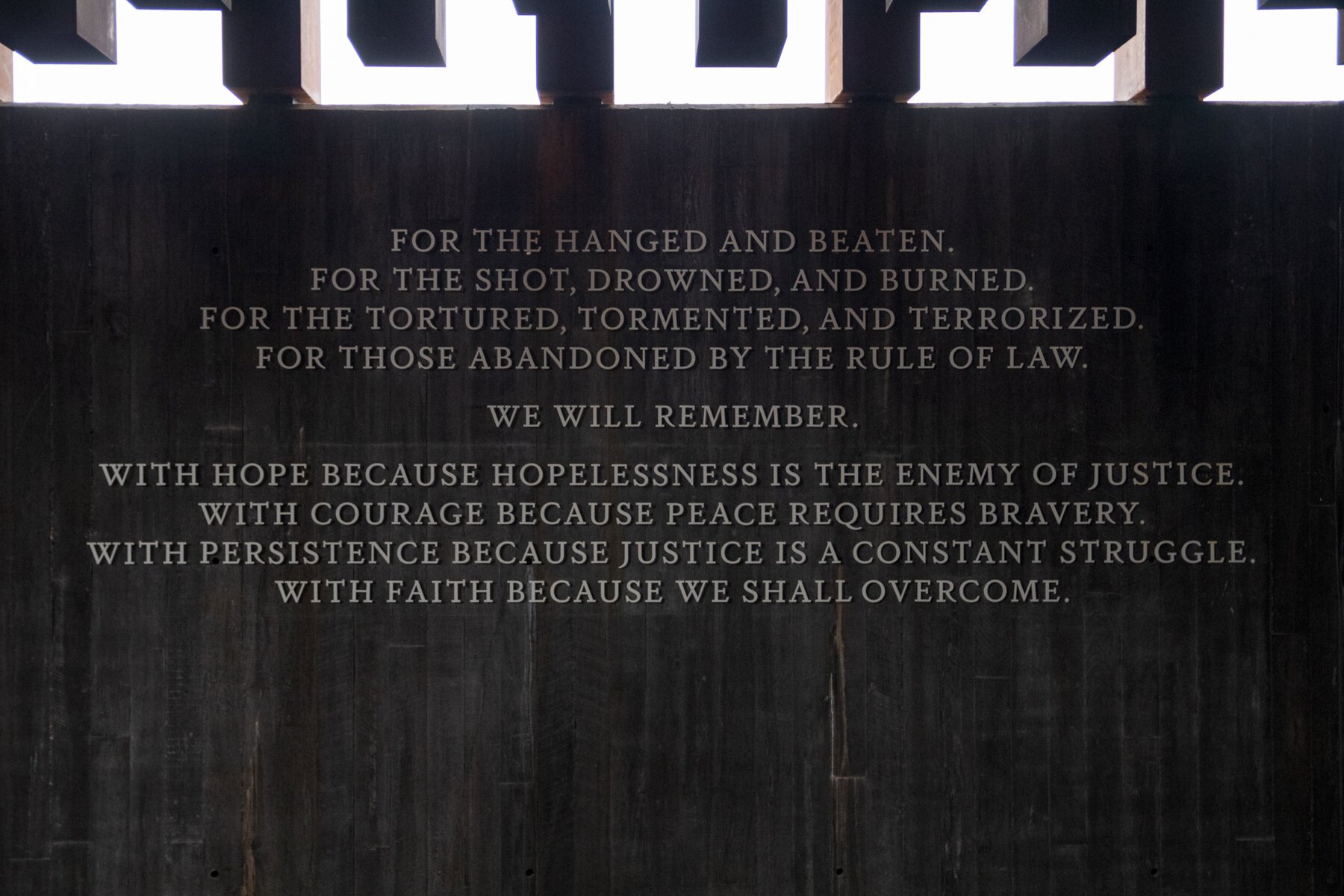

The Memorial for Peace and Justice was conceived and designed in collaboration with the MASS Design Group with the hope of creating a somber, meaningful site where people can reflect on America’s raw history of racial inequality and injustice. Within the memorial are 800 six-foot monuments, each one suspended to represent every county a lynching took place in the U.S. with the names of the thousands of victims etched in the weathered steel monuments.

Around the memorial square lay duplicates of the 800 monuments ready to be implemented through the EJI’s Community Remembrance Project. Their goal is for these 800 communities to recognize their local history head-on, organize soil collection ceremonies from each site, erect historical markers, and engage local students to support the development of local, community-led efforts to engage with and discuss past and present issues of racial justice at home. Once the community has been engaged, EJI would arrange their corresponding monument to be transported and placed at home in the community.

This period of racial injustice and terror lynches hasn’t gone away, it’s just evolved post-WWII in the form of systematic poverty, racial bias, unjust criminal justice system, and above all else: violent policing. The installation entitled “Rise Up” by artist Hank Willis Thomas addresses this modern version of racial terror throughout America in cities like New York, Maryland, Ohio, Missouri, California, Arizona, New Jersey, Wisconsin, Oklahoma, Florida, South Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, and most recently: Minnesota (plus, so many more).

Today, the evolution of the Civil Rights movement has become known as Black Lives Matter and it’s on each and everyone of us to live that out on a daily basis. As a white male, it’s not easy to know what to do to help, but organizations like Showing Up for Racial Justice, Alliance of White Anti-Racists Everywhere, and others are trying to help educate, engage, and enlist the support needed throughout the country to create the systematic change for equality.

In addition to the “Rise Up” installation, artist Dana King commemorates the women of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in her piece “Guided by Justice” and the memorial has a reflection space in honor of Ida B. Wells that enables visitors to meditate on this experience they just walked through on these six acres that overlook downtown Montgomery.

While the neighborhood around the memorial seems to be still in gradual repair, we want to make sure to note that Montgomery and Alabama as a whole is bigger than its history of racial struggle. While we know there is plenty to celebrate and commemorate, our visit and focus on this experience is centered on this particular, and extremely important, piece of our country’s ongoing history.

SEVERAL MONTHS LATER…

Fast forward five months to May 2019 — we survived one of the coldest Michigan Winters on record, were living in the basement of Kendra’s childhood home with her parents, and were still without funding to complete the tour. Our Airstream was being stored in Florida, which we had to extend its storage date time after time after time. We purposefully stored it down there so that we would be “forced” to finish the tour by picking up where we left off. We feared that if we would have brought it home with us in January when funding first ran dry, that it’d be too easy to not finish the mission (by possibly being lured back into a corporate career, which almost happened with an “ideal” job offer from Chaco).

Our timeline (and patience) was running shorter and shorter. We had some Airstream warranty work that was getting close to its two-year expiration date and our truck lease was also drawing to an end, plus we wanted to rescue it from the summer sun and heat in central Florida soon than later. We decided we needed to drive down and get it, and while we were, we’d figure out a way to conduct a couple more state projects.

On the drive down, we planned to conduct our STATE 38: ALABAMA project. We got connected with designer Christian Dunn, who taught Graphic Design at Jacksonville State University. He shared with us that his mentor happened to be a Green Beret - the Special Forces of the U.S. Army, and also a real-life cowboy.

Christian “roped” his boss Seth Johnson, who is the head of the JSU Art & Design Department, to participate as our project videographer. Since we didn’t have our Airstream with us on the way down to Florida, they generously hosted us in a local hotel for a couple nights as we conducted the two day design process on campus. Their support was crucial because while sitting in the first project day, I received a bank notification that our personal bank account was overdrawn. Funding our own way down to Alabama put us in the red — things were that direr for us at the time. Thankfully, my dad was able to lend us some money to make it the rest of the way, but man, receiving a notification like that has been one of the worst feelings and moments of my life thus far. We’ve been deep in this 50 States project since 2017, and now we’ve gotten even deeper in it yet just trying to make it through to the end.

If it was easy, everyone would do it. When you believe it’s your purpose, it’s harder NOT to do it. We’re dedicated to figuring out a way to make it happen, but that doesn’t mean we’re still not looking for support of [HAS HEART] to complete this nationwide mission.

There are too many great people, too many communities like Jacksonville, and too great a need to connect Americans like never before to NOT finish our mission. As Jacksonville rebuilds from the tornado that tore through the campus in 2018, we as a country also need to find solutions to rebuild in numerous facets. We all have a role to play in healing our communities and country, it’s up to us to find our purpose and live that out on a daily basis.

Thank you, Alabama. The struggle may continue, but it’s at least it’s a struggle towards progress.