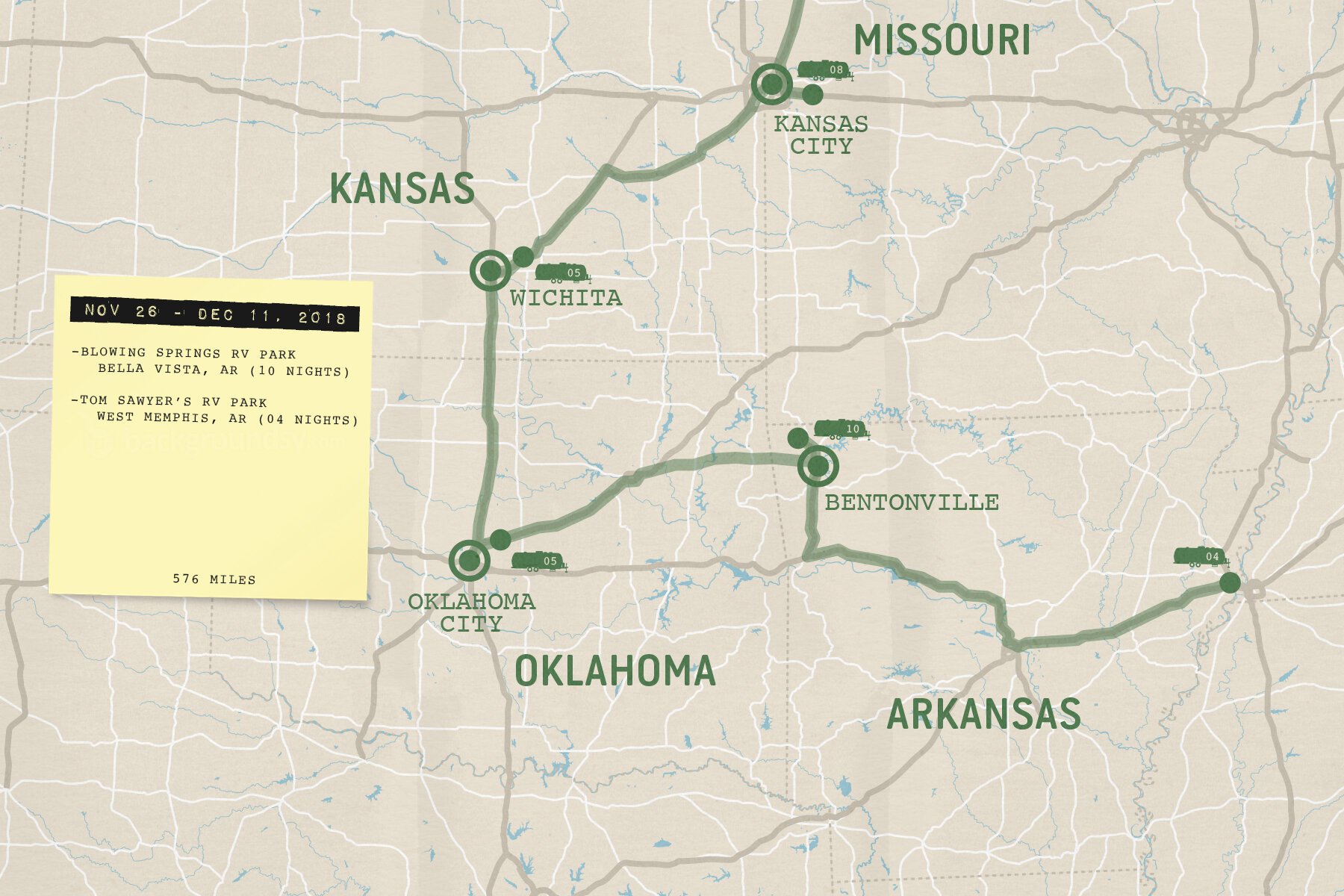

35/50: Arkansas

Fresh off a Thanksgiving break and a quick trip to and from Seattle, we flew back to Oklahoma City to pick up Noel and our Airstream, and hit the road for STATE 35: ARKANSAS.

A couple of years earlier, we had met someone at the Schultz Family Foundation who was a key person that got us our first grant to host the pilot projects of the 50 States: Veterans + Artists United tour in early 2017. Sometime later, she notified us that she had accepted a position at corporate Walmart in Bentonville, Arkansas, and welcomed us to share a drink on her porch whenever we’d be passing through.

Well, we did just that. But instead of a drink on her porch, we enjoyed brunch together, nearly two years after we first pitched her our ambitious mission. It didn’t take long for us to look around and notice we were in Walmart Country. Everywhere we looked, Walmart was more than likely involved in it somehow. Whether it was a gas station, an office building, a school, a restaurant, downtown stores, or public parks — at one time and in one way or another, Walmart had a hand in it.

Without going into the good, bad, and ugly parts of Walton’s riches, let’s proceed throughout Bentonville and get a taste of NWA (NorthWest Arkansas) — not N.W.A. from Compton.

I suppose the best place to start is at the heart of the town, and the site where it all began: Walton’s Five & Dime general store on Bentonville’s central town square, which of course now is the Walmart Museum. Started in 1950 by Sam and Helen Walton, it still has the original red and green floor tiles that are just as mismatching as when Sam laid them. He was apparently a very, very frugal man who sacrificed whatever he could in order to offer lower prices, something Walmart still certainly does today.

On a separate note, I’m a fan of the red truck that’s always parked out front.

We did stumble upon Onyx Coffee Lab right around the corner from the town square, which we were big fans of.

We were later invited by our project videographer Tanja Heffner and her partner to check out The Holler — A Local Hangout. We dug it. Not only did they have the vintage, Wes Anderson-like camp vibe that we can appreciate all of its design details, but it’s multi-use day to night, weekday to weekend use is unlike any other we’ve come across on the tour.

Within their large space, they have a coffee shop area with plenty of work and informal meeting spaces to use during the morning and afternoon, they have food service and plenty of booths and dining tables, they have indoor bocce ball courts in the center surrounded by bar seating for leagues and parties, and they have a large bar area for their evening customers. Like I said, they have something for everyone from when they open at 7AM to when they close at 1AM. The Holler is one of many NWA endeavors by the Ropeswing group, who seem to have a knack for creating enriching experiences for the community.

The Holler is one tenant within the 8th Street Market compound that also houses the craft and homegoods store Hillfolk, which is where I bought a Sashiko handkerchief embroidery kit that has since hooked me small handcrafted projects and away from the computer. There is also a mexican restaurant, brewing company, bodega, juice company, specialty chocolate bakery, ramen restaurant, yoga studio, food trucks, and weekly farmers markets within the strip.

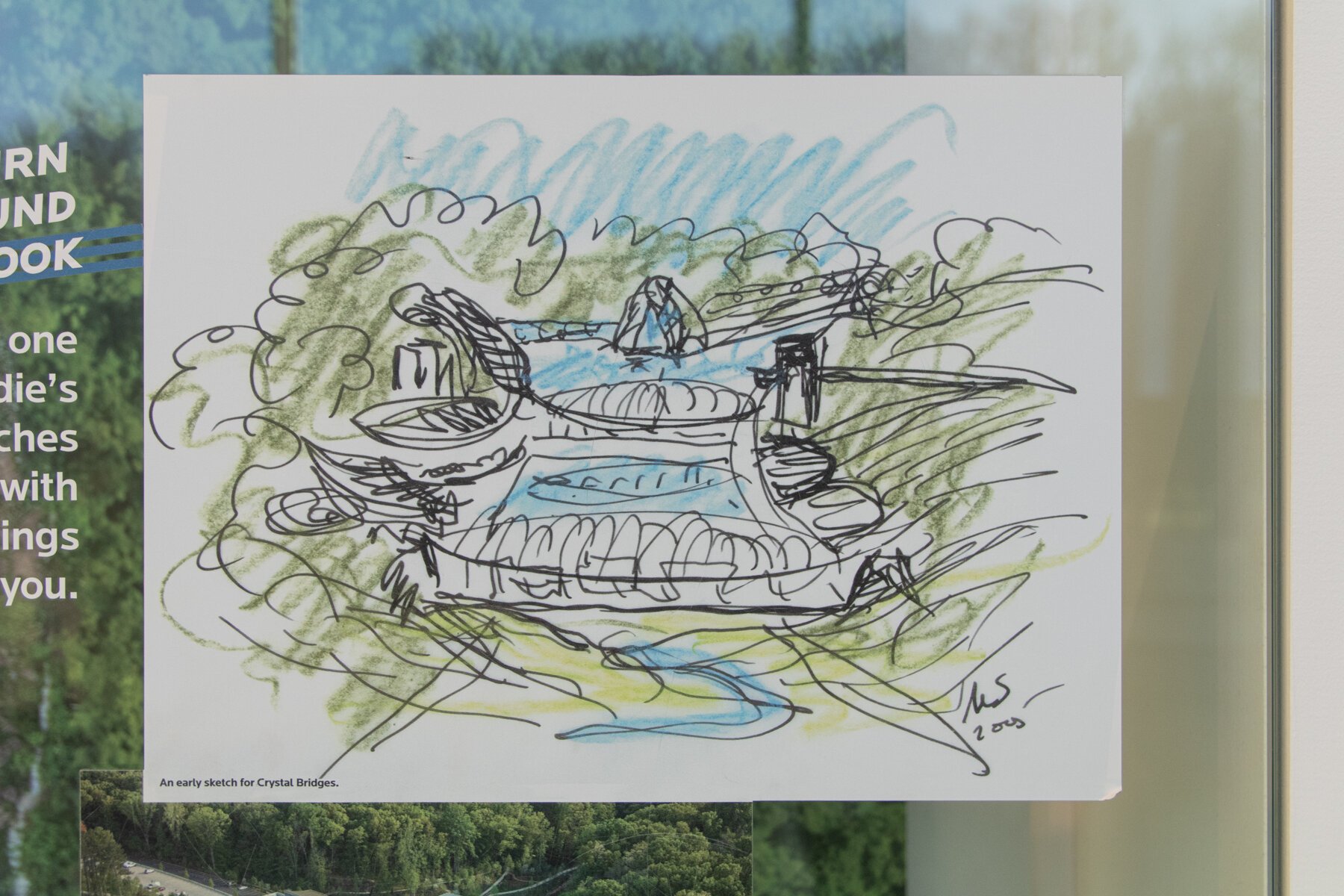

The gem of NWA has to be the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Founded in 2005 by Alice Walton, the 120 acres of land features numerous nature trails around the two spring-fed ponds that architect Moshe Safdie designed around to house a permanent collection that spans 500 years of American art.

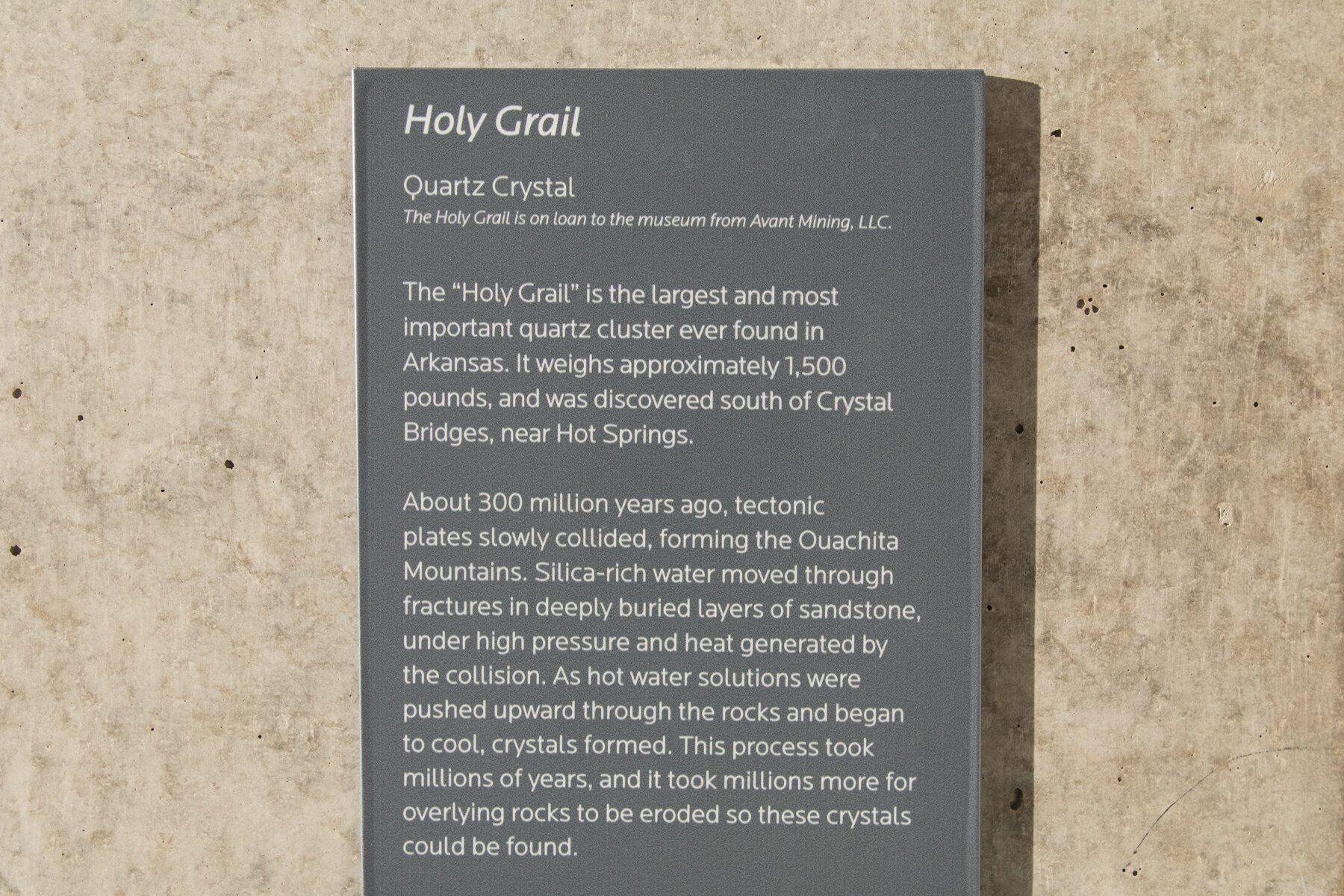

Pretty soon after you enter, you’re introduced to the “Holy Grail” quartz cluster that weighs in at around 1,500 pounds discovered nearby near Hot Springs. The plaque on the wall next to it provided some great scientific insight into how something so beautiful and so raw came to be by Mother Earth:

About 300 million years ago, tectonic plates slowly collided, forming the Ouachita Mountains. Silica-rich water moved through fractures in deeply buried layers of sandstone under high pressure and heat generated by the collision. As hot water solutions were pushed upward through the rocks and began to cool, crystals formed. This process took millions of years, and it took millions more for overlying rocks to be eroded so these crystals could be found.

Now, if that’s not poetic and amazes you in any fashion, then I don’t know what else could. Nature is crazy, nature is beautiful, and nature is worth us protecting.

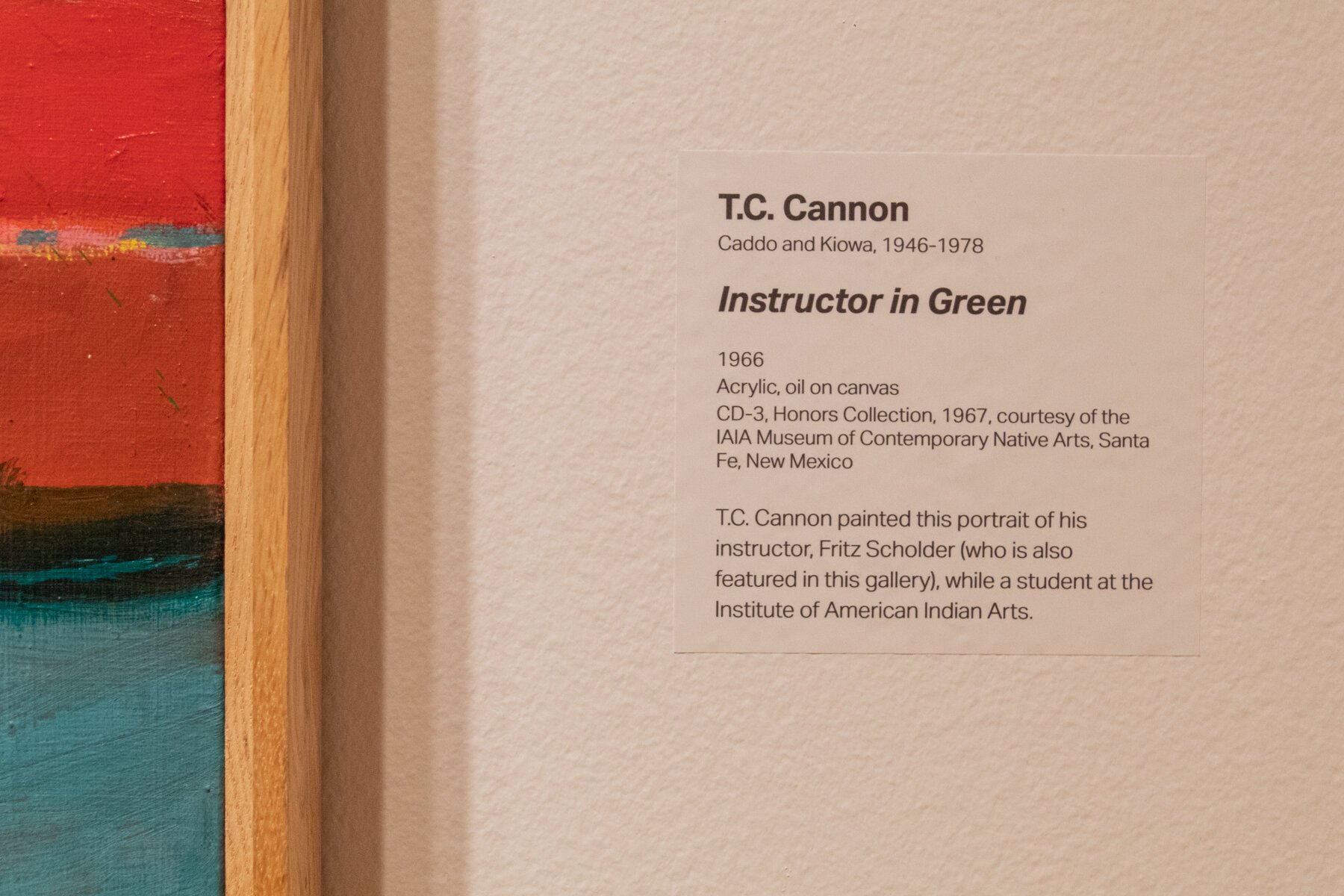

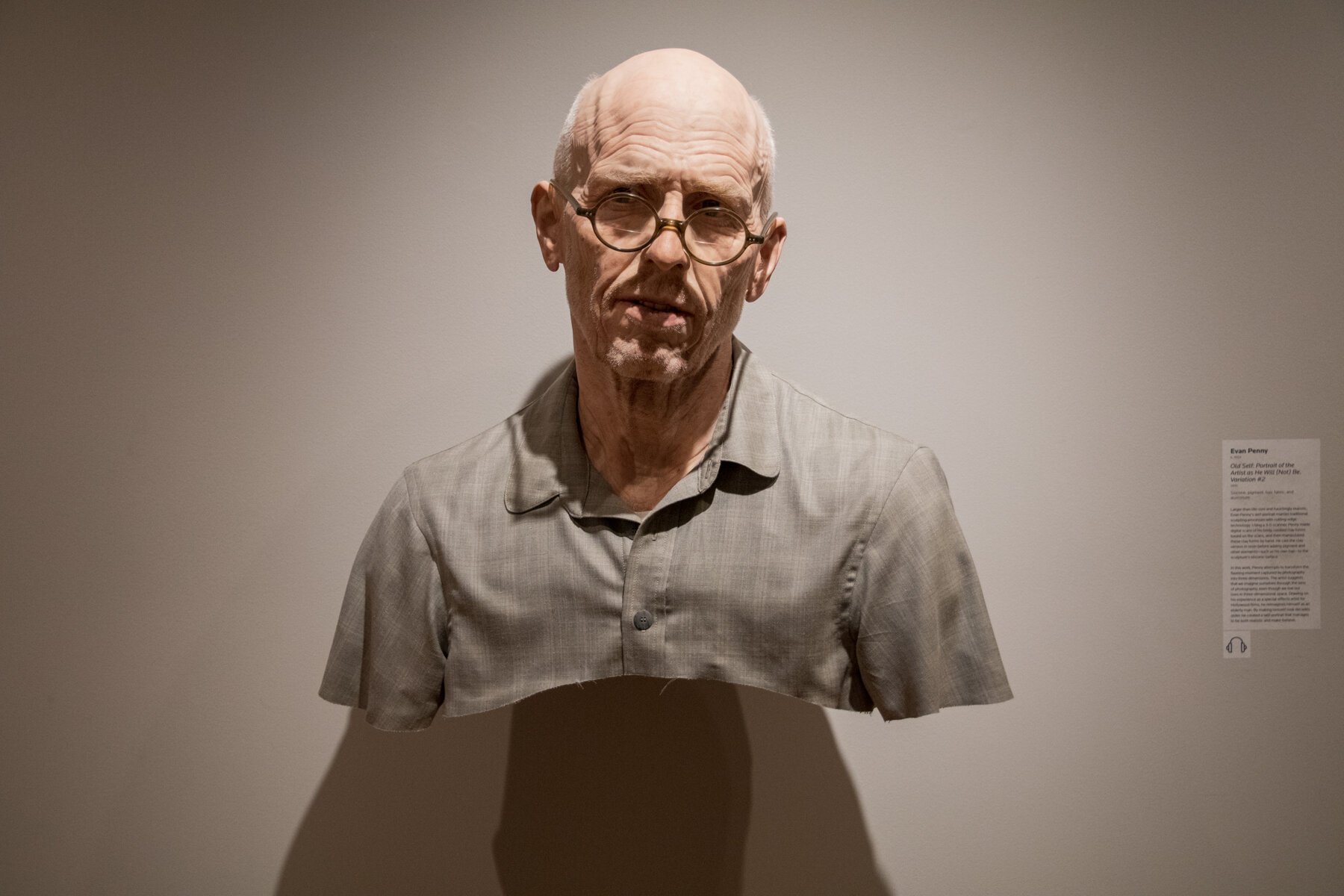

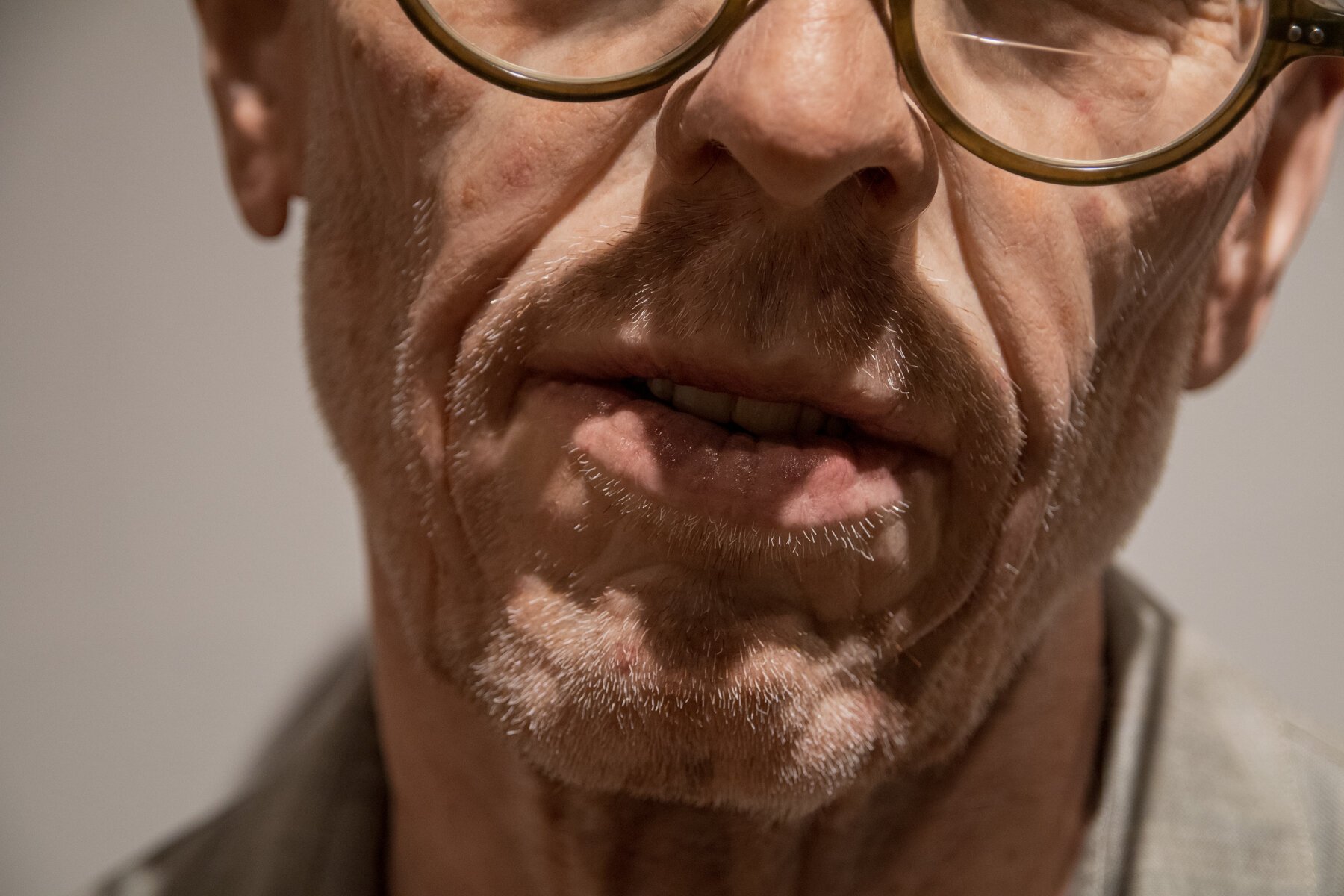

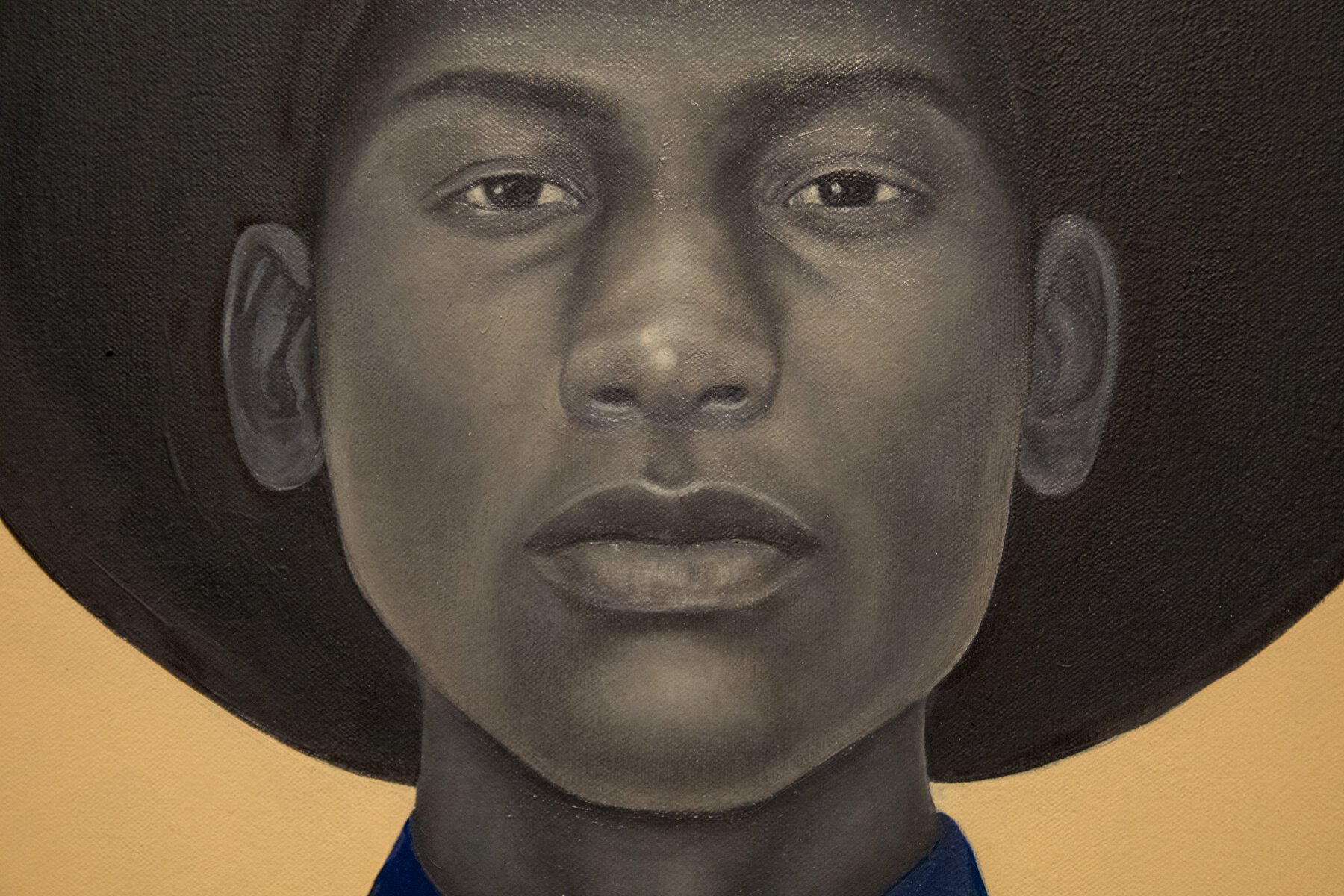

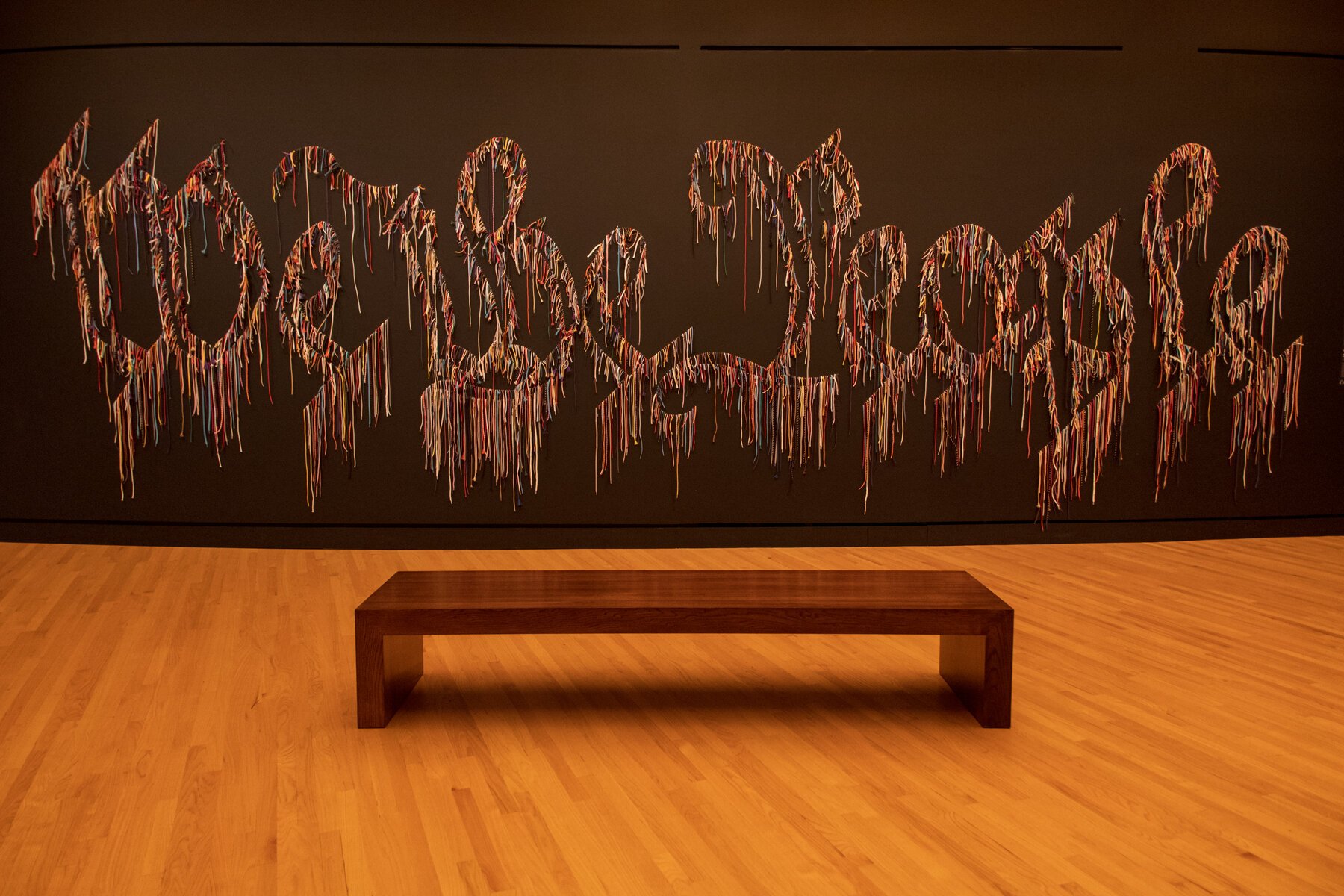

Another piece of our country worth protecting is the culture that lived on this land before it was colonized away from them. We happened to be there during the temporary exhibit “Art For a New Understanding: Native Voices - 1950s to Now,” which happened to feature works from Native artists that went to school at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, where we conducted our STATE 18: NEW MEXICO project.

The exhibition featured over 80 artworks from the 1950s to today, including paintings, photography, video, sculptures, performance art, and more, all created by Indigenous U.S. and Canadian artists.

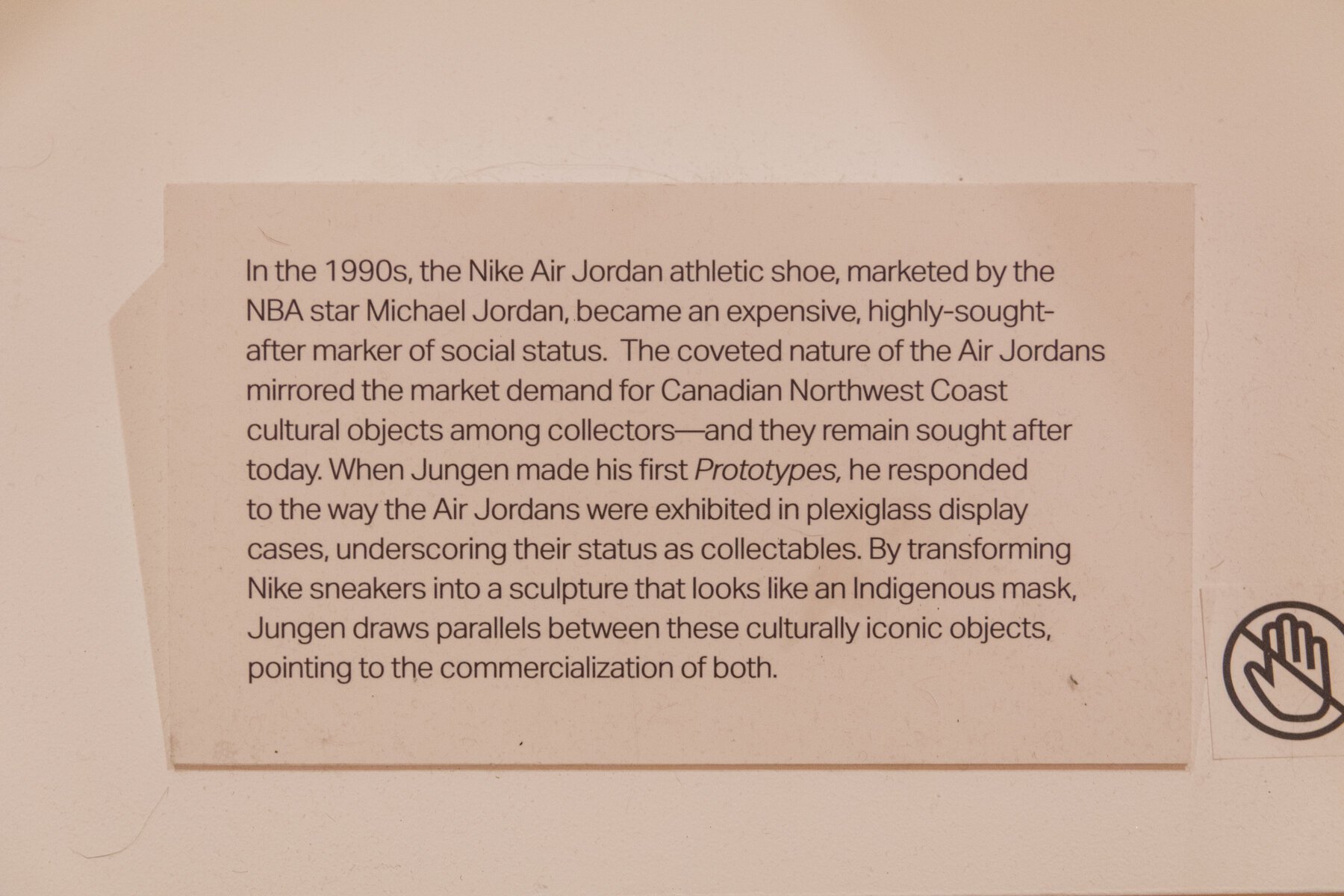

One of the contemporary installations that (of course) caught my attention was by Brian Jungen (Dane-zaa / Canadian, b. 1970) and his “Supersize the Light in All Directions” installation of a variety of Jordan’s cut, sliced, glued, stitched, and arranged into sculptures that resemble Indigenous masks.

The parallels between Air Jordan basketball shoes and Canadian Northwest Coast cultural objects may not seem very close together to the average viewer, but Jungen’s Prototypes compare the modern mass-produced consumer good with the historic hand-crafted art, suggesting subtle layers of references to sports as a replacement for actual battle, including America’s appropriation of Indigenous personas for a variety of high school, college, and professional sports teams.

Speaking of America’s appropriation of Indigenous personas as mascots and team characters: seeing the collection of sports team memorabilia in this piece from the Washington Redskins, Cleveland Indians, Kansas City Chiefs, Florida State Seminoles, Illinois Illini, and others was a sad but powerful statement. Hopefully, we Americans will wake up to this crudeness and realize our mistakes, starting with this one.

Many other works celebrated Indigenous culture, life, and imagery.

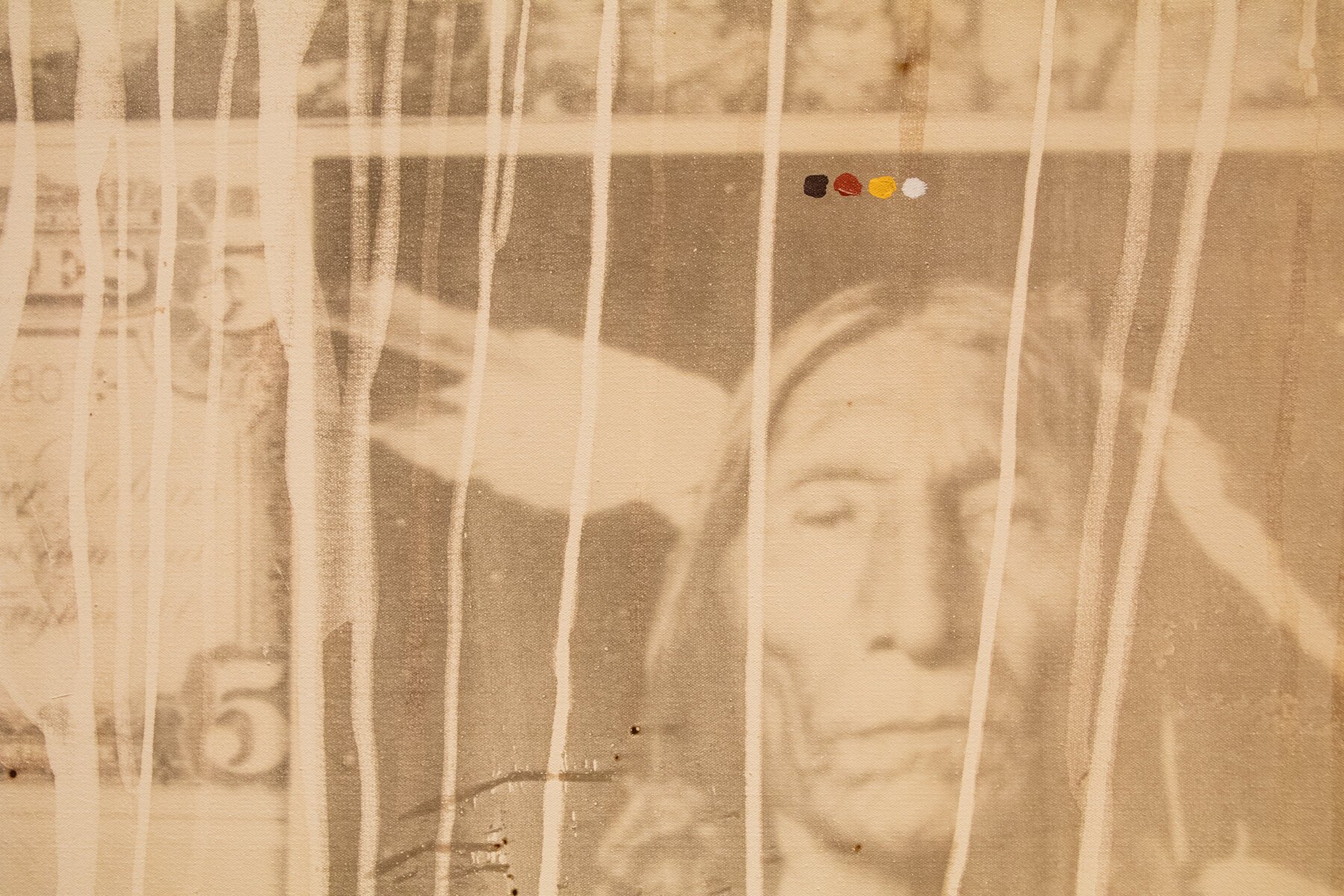

Another piece that I enjoyed admiring up-close was the Salvador Dalí-like artwork by Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun (Coast Salish and Okanagan, b. 1957), who has said that it’s been his life’s goal to portray the negative and positive realities of this world in a style that is influenced by his native Northwest Coast imagery and ovoid shapes through a Surrealist style:

“If you only allow colonialists to record history, they record it to their own glorification. I wanted to take that position of power, of historical painting, and put it into my own hands — take possession of history.”

— LAWRENCE PAUL YUXWELUPTUN

After spending quite a bit of time walking through the “Art For a New Understanding: Native Voices - 1950s to Now” exhibit, we started moving into the permanent collection of Crystal Bridges, beginning with some of their outside pieces throughout the numerous nature trails.

The BIG highlight for me was the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Bachman-Wilson House. The Usonian house was initially built in 1956 on the bank of the Millstone River in Somerset County, New Jersey, but in 2013 it was acquired, disassembled, moved, and rebuilt at Crystal Bridges. We weren’t allowed to take any pictures inside, but the museum worked with Google Maps to create a “street view” virtual tour of it. Unfortunately, even the virtual tour doesn’t allow us upstairs, but at least it captures some of my favorite features of the home interior that I wasn’t able to take with me: the long built-in couch bench and bookshelf, double coffee tables (with stools), the wall of windows overlooking nature, floating staircase, open fireplace, and the cozy corner kitchen. Architectural Digest has pictures of the upstairs bedrooms, which are just as good as I'd imagine.

FLW was my first introduction to architecture, thanks to my favorite high school teacher, Mr. Messmore, while we were in the library one day. He suggested I look up Frank Lloyd Wright in the library (side note/flash to the past of what it’s like to look something up in real life via the Dewey Decimal System), which a few years later almost led me to study architecture in college at Lawrence Tech University near Detroit instead of Advertising and Public Relations at Grand Valley State University in Grand Rapids.

To this day, I sometimes consider going back to school for architecture. Maybe.

Once it was basically too dark to see much outside, we moved back indoors to explore more wings of the permanent collection.

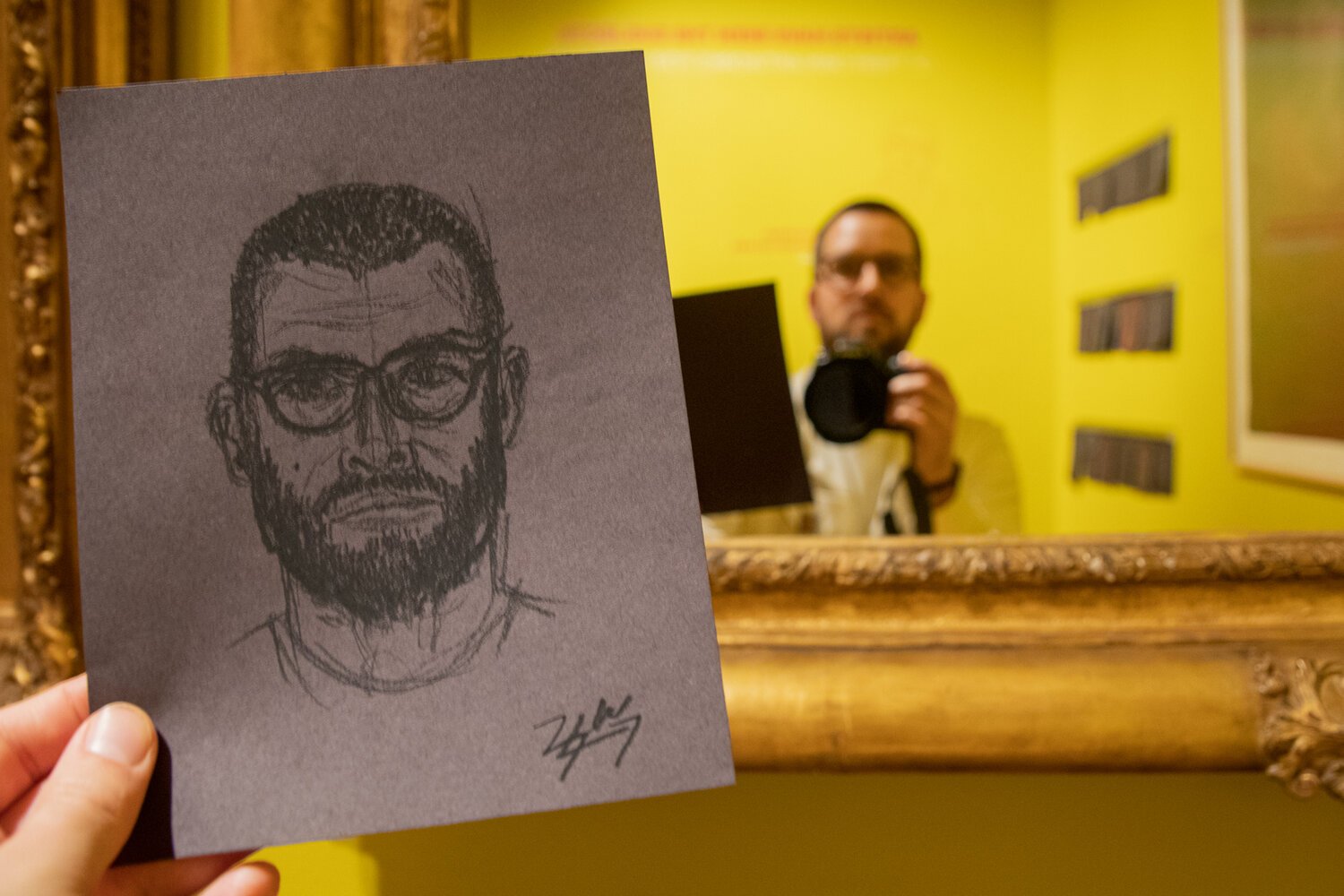

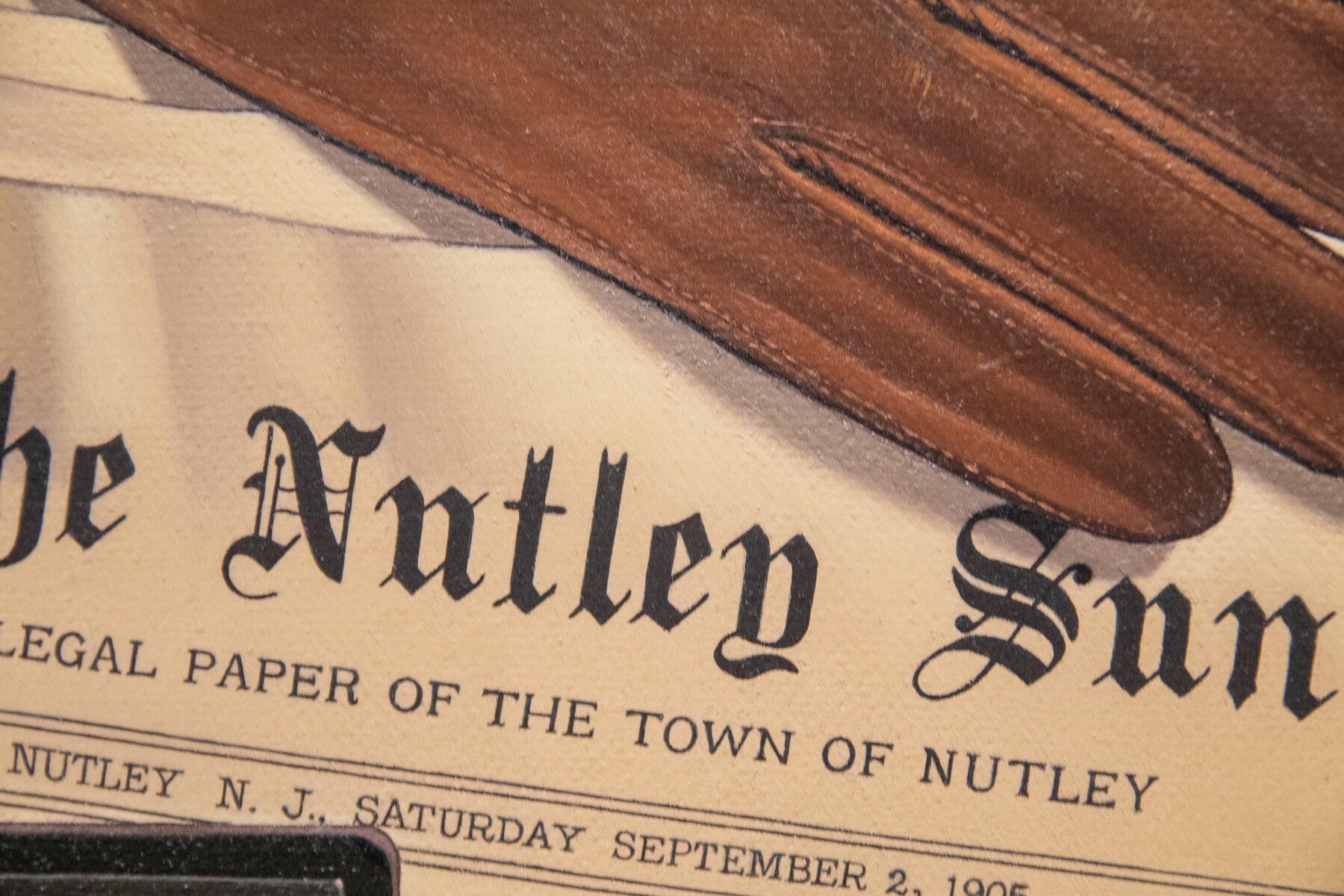

My favorite part of visiting museums, whether it’s large museums like the MOMA in New York, smaller ones like Yale University Art Gallery in Connecticut, or niche collections like the Desert Museum in Arizona, is looking at the artist’s execution, brush strokes, colors, and details that make up the larger picture and statement. Sometimes it’s hard to resist touching it, but then you’d get thrown out and not allowed in any more museums, and that wouldn’t be worth it.

I also enjoy seeing how museums try to engage with their viewers and make the art accessible, relevant, and engaging. One of the areas had a self-portrait station that enabled children and adults to draw themselves using the mirrors and supplies laid out. My quick sketch looked more like a police sketch, but it was still fun to interact with the art around me.

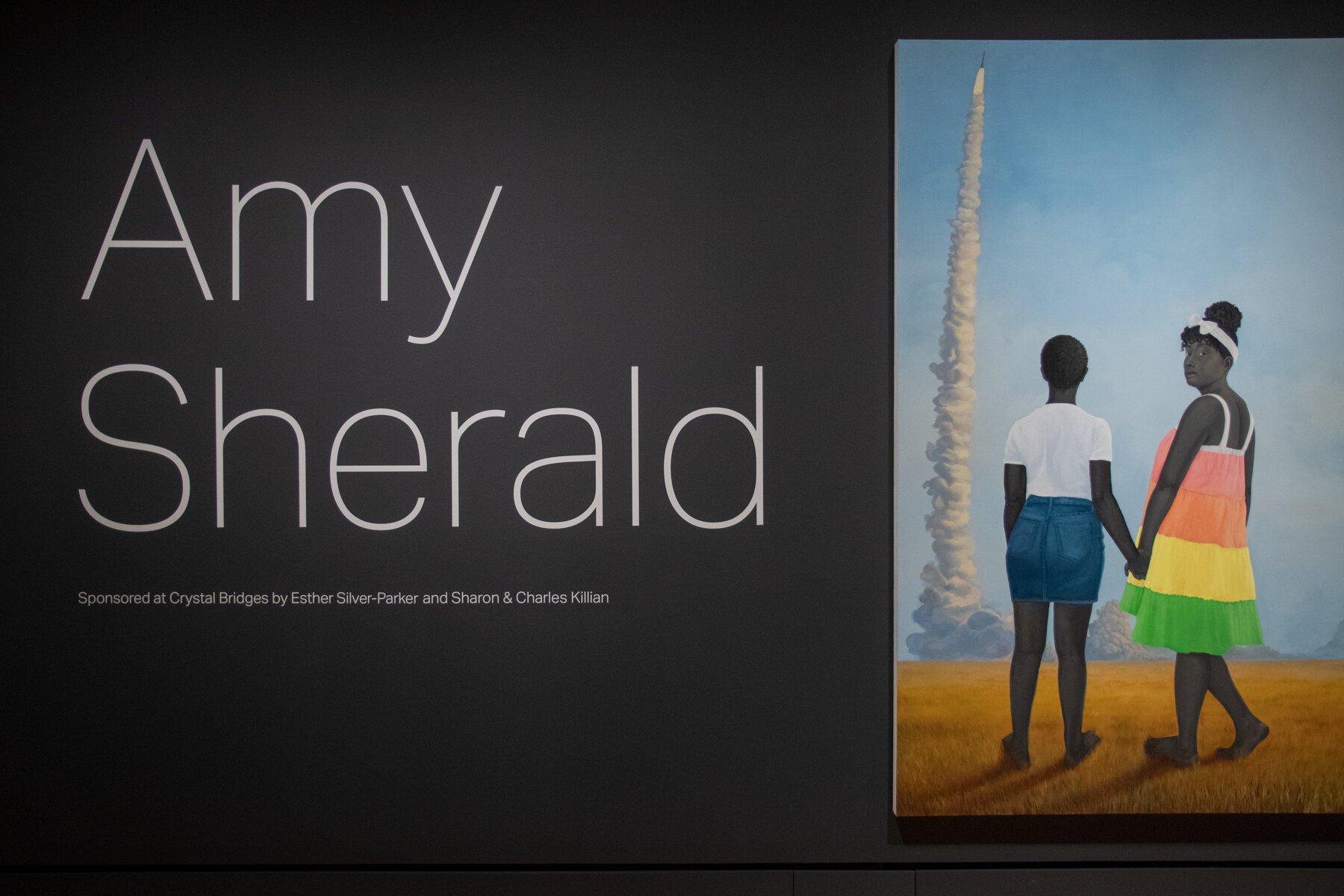

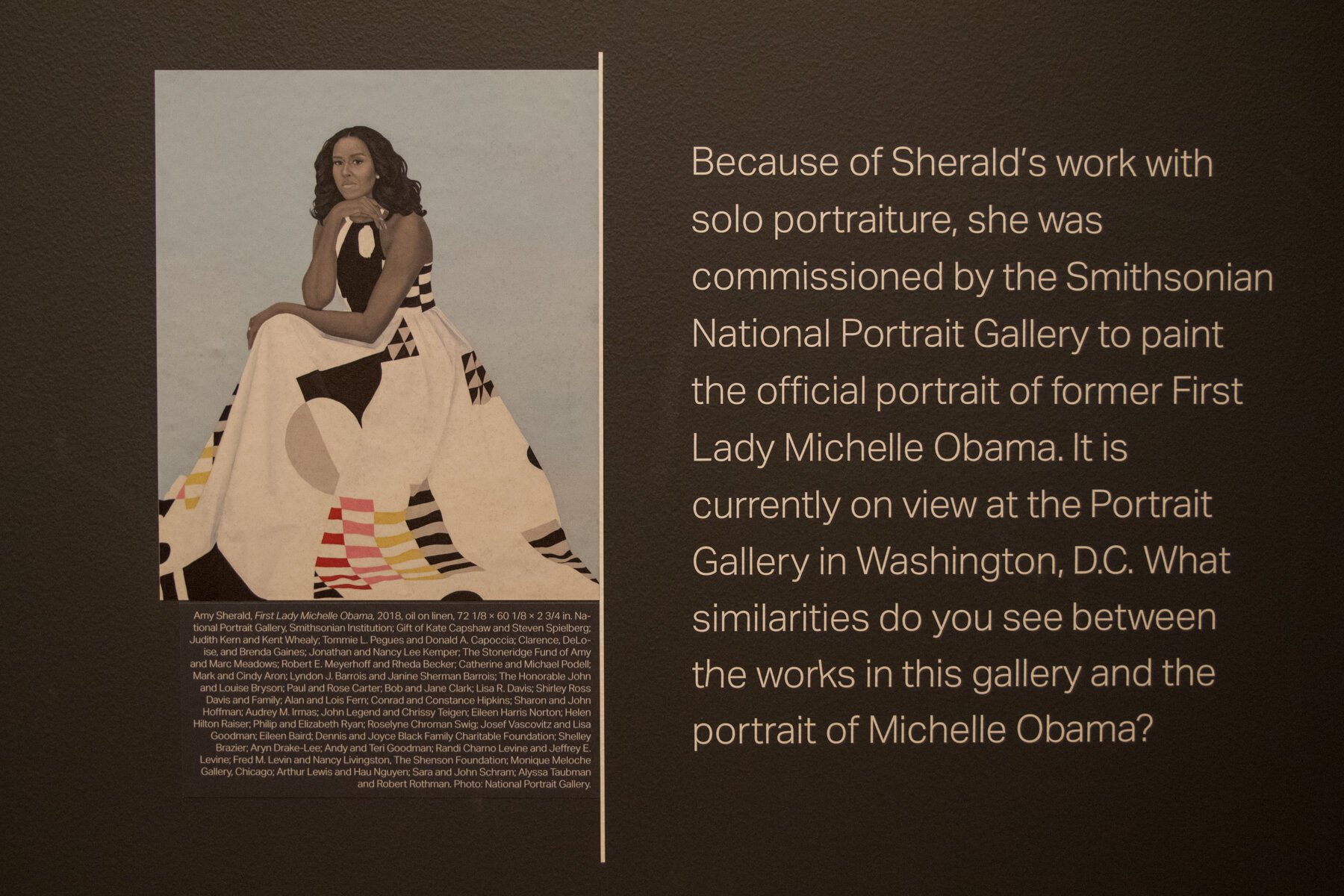

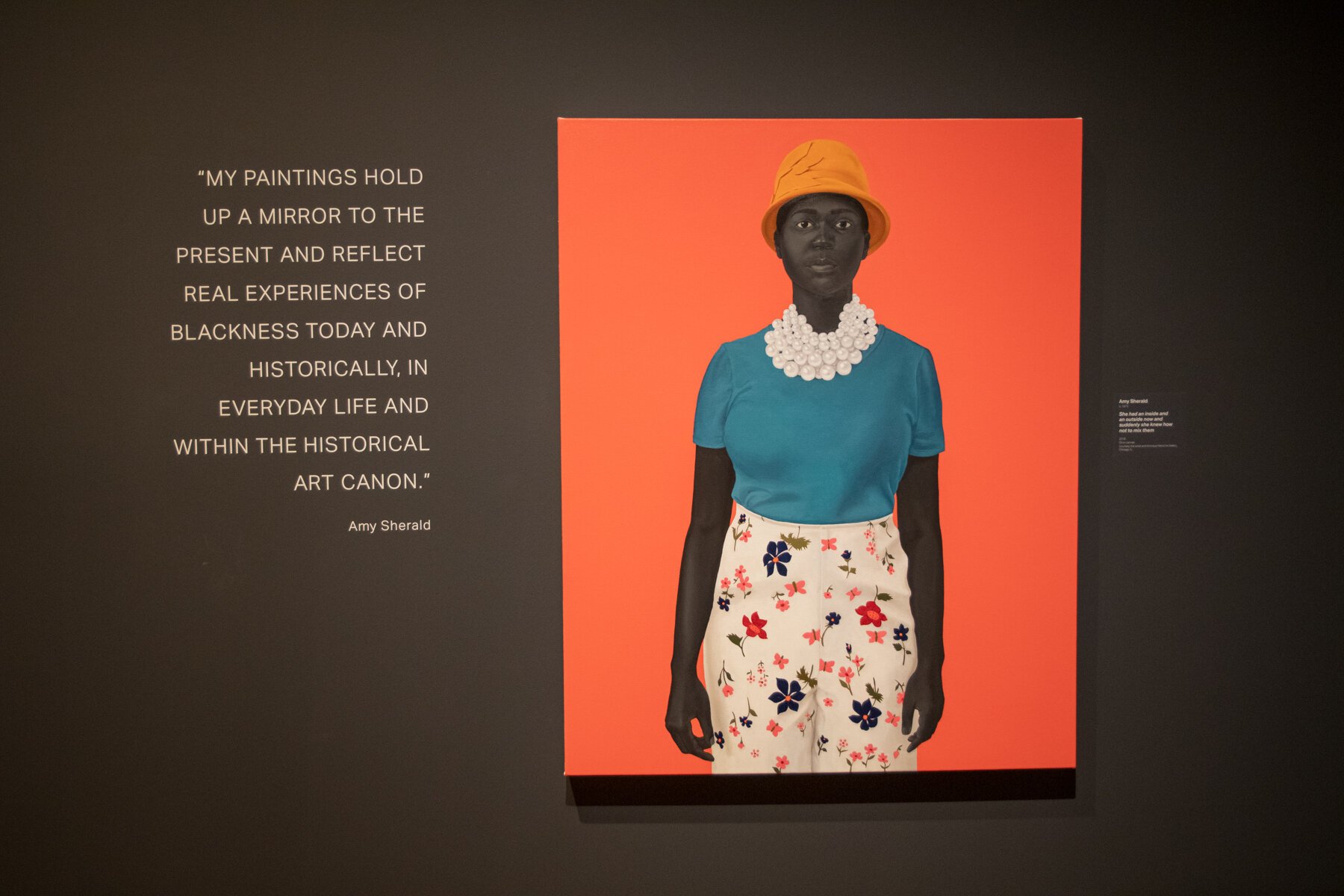

It’s always exciting to see modern pieces or artists’ works relevant to today’s culture. We walked around the corner and immediately recognized the style of Amy Sherald (Columbus, GA b. 1973), who most notably was commissioned to paint the official portrait of First Lady Michelle Obama.

Similar to how artist Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun’s mission is to capture cultural history with his power of the brush, her work is meant to authentically represent what it means to be black in America today.

“My paintings hold up a mirror to the present and reflect real experiences of blackness today and historically, in everyday life and within the historical art canon.”

— AMY SHERALD

A couple of days before we were scheduled to leave Arkansas for our next state, the area got hit with a massive storm. And when I say storm, I mean there were numerous tornadoes and extreme amounts of lightning throughout the area. Growing up in Michigan, there’d be the occasional tornado warning every few years where we’d have to go down to the basement for an hour or so until the threat passed. But being in an Airstream trailer, there was nowhere to go. We were in a steel tube full of windows and surrounded by trees. It was a tense few hours as we huddled on the floor in the center of the trailer between the shower and bathroom.

Obviously, we’re here to tell the tale, but between the three of us, Noel was the only one not tense and worried about being rolled away or fried like campfire potatoes. The next morning we surveyed the damage around us and were thankful there was no hail or tree damage to the Airstream or the truck.

Onward to STATE 36: MISSISSIPPI.