36/50: Mississippi

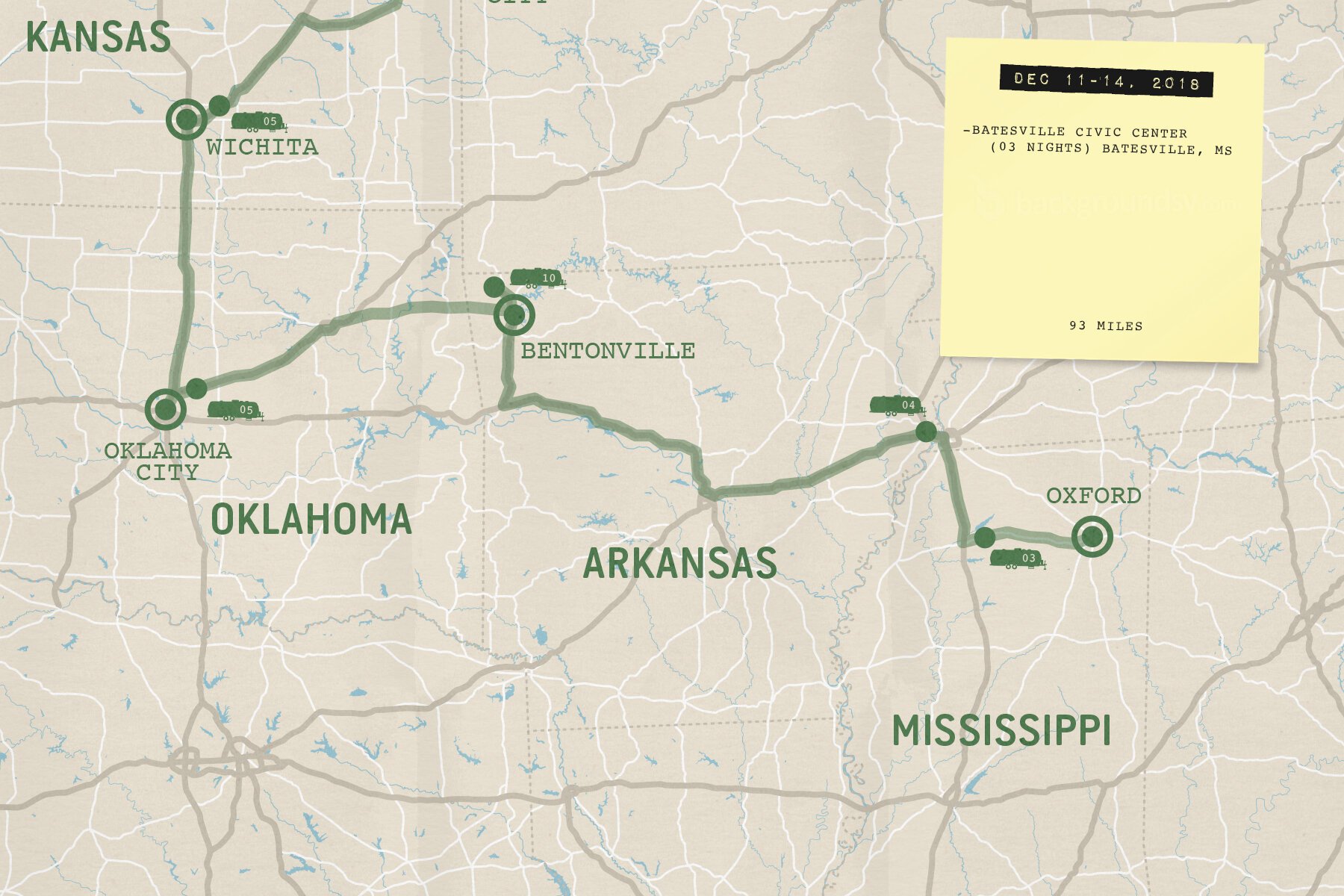

After our time in STATE 35: ARKANSAS, we technically spent four more nights in Arkansas along the Mississippi River on the tri-border of Arkansas, Mississippi, and Tennessee. For this blog post, we’re going to count this as our time spent in Mississippi, even though technically we bounced back and forth between the three.

I want to make that a point because this area is so much more than just locations on a map. This area is steeped in so much of our country’s history. At 2,348 miles long, the Mississippi is the second-longest river in the United States. Its drainage area is about 1,250,000 square miles, making it the third largest in the world. It starts all the way up north in Minnesota and runs south, flowing out into the Gulf of Mexico. For obvious reasons, the Mississippi was a significant vein of transportation and commerce in North America, especially before the railroads.

But, its history is also very dark. Among the Mighty Mississippi’s importance for commerce in our early history was its role in the slave trade. In 1820, the state of Mississippi had around 33,000 slaves, but by 1860, that number grew exponentially to over 430,000 slaves — making it the largest slave state in the United States. The river and towns along it were how the slave trader expanded further inland and further south. Its largest inland slave port was in Natchez and its Forks of the Road slave market.

Our first encounter with slavery in the south was when we were in STATE 14: SOUTH CAROLINA, but now we were deeper into it — which was an unsettling feeling as we pulled into Tom Sawyer’s RV Park.

Being so close and on such flat land along the Mississippi, this area is prone to seasonal flooding. We realized that once we pulled in and noticed the park office building on wheels, the laundry center on very large stilts, and even a few tree house cabins nestled amongst the bare trees. Even Google Maps recognized this area as a flood zone because it said technically our blue dot was underwater.

Once we set up camp and were getting settled inside, we heard this very low rumbling rhythm. We went outside to investigate and saw tugboats and barges motoring up and down the water highway. This was modern life on along the Mississippi River.

Just along the river bend from the RV park was the city of Memphis, Tennessee — at night we could see the flow of its lights above the treeline to our East. We took a 20-minute drive across a few bridges to take in a few Memphis landmarks, starting with the King and his Graceland. We didn’t feel strongly enough to pay the $40/person entrance fee (which is their cheapest option), so we just peered over the stone wall covered in graffiti tags of “Canada <3’s Elvis” and “MB was here” and saw a glimpse of the house and its annual Christmas nativity scene staged on the front lawn. That was enough for us as we drove past his plane across the street listening to an ongoing “This is Elvis Presely” playlist on Spotify.

Although Memphis and its famous Beale Street is touted as the “Home of the Blues,” we weren’t quite up for its late night crowds and buzz this time around. Although it was cool that our videographer, Chris Porter of Creative Punch Marketing Group, from our Mississippi project had recently designed the Beale Street neon archways. We’ll save this taste of Memphis for our next visit.

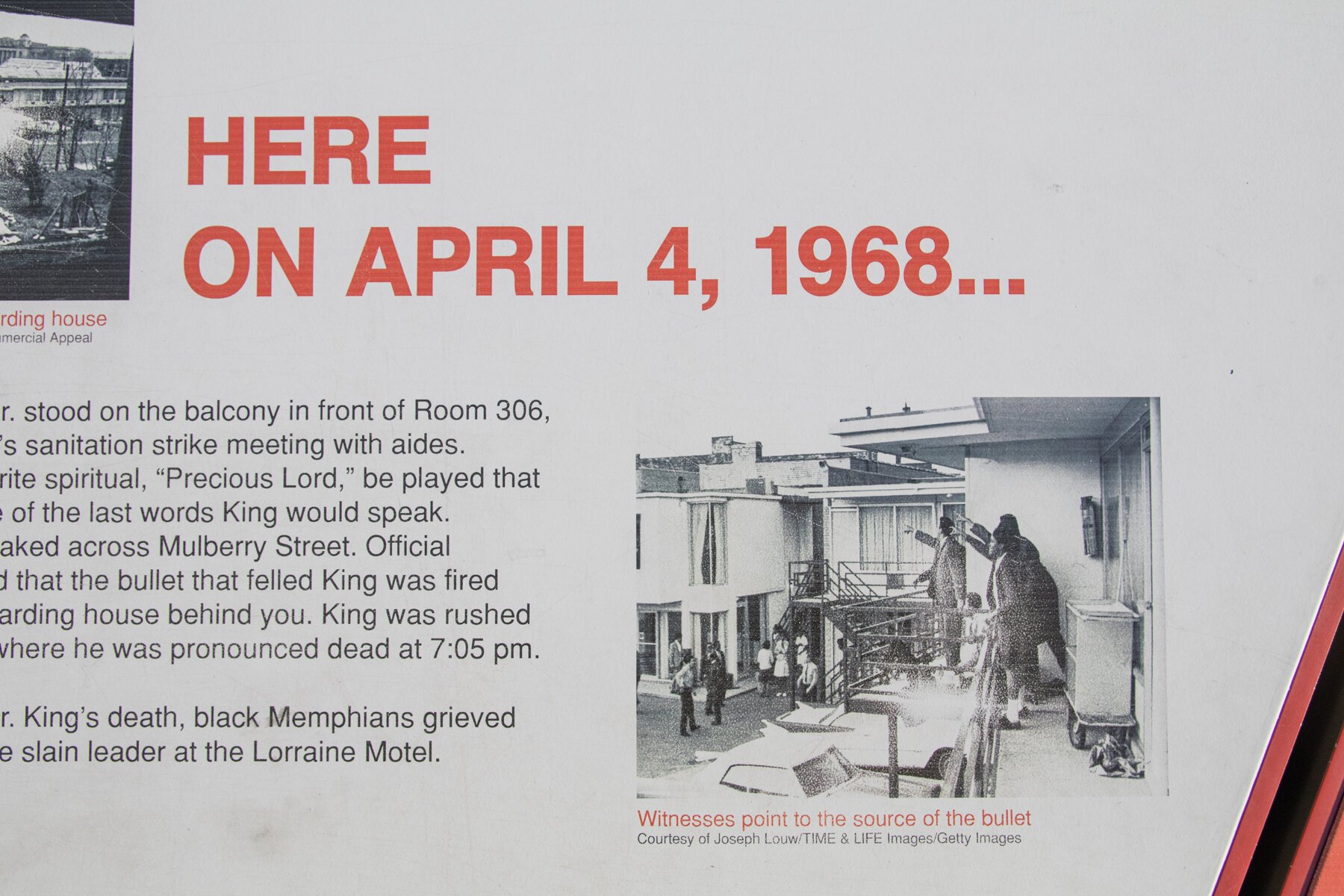

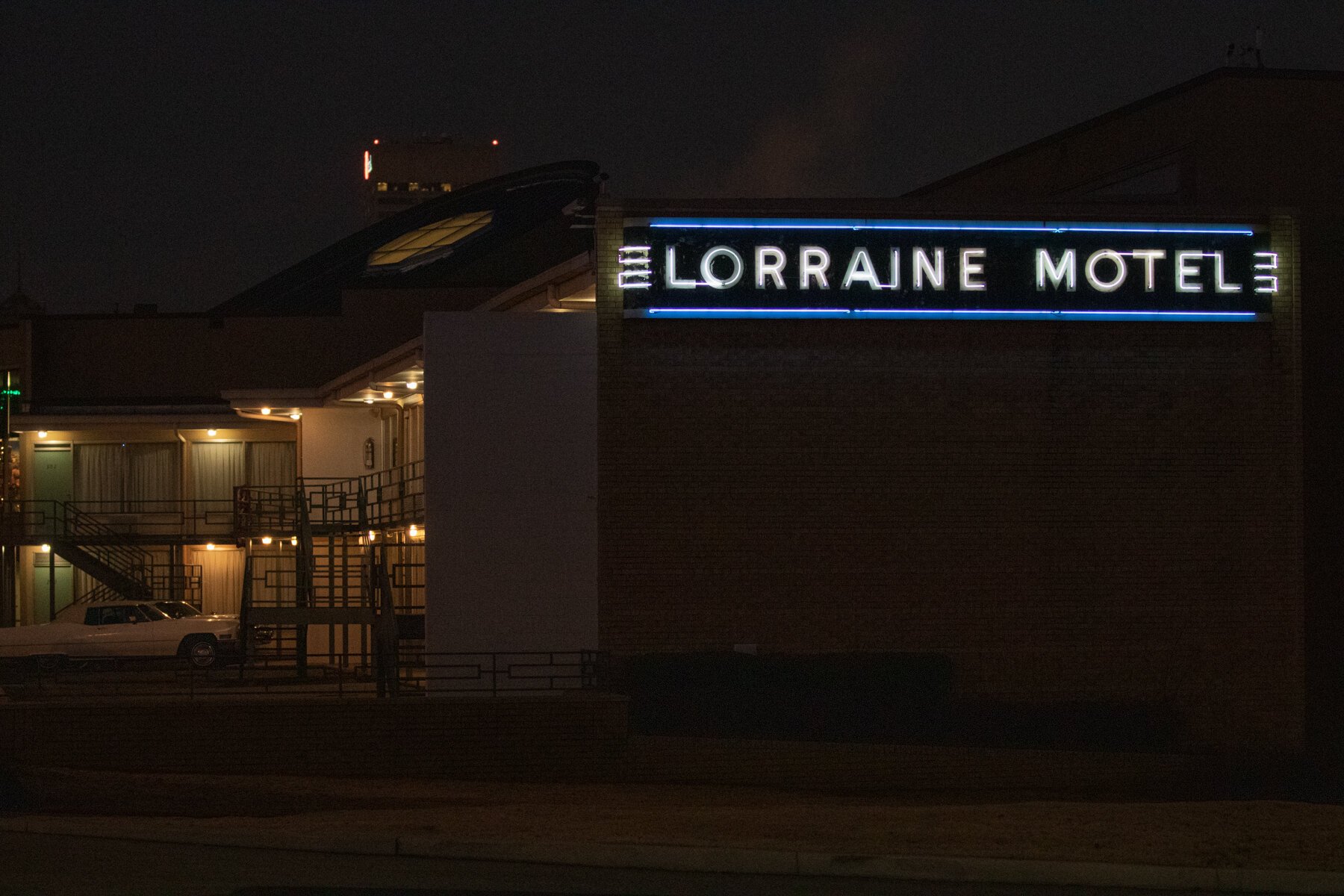

Our main mission for visiting Memphis was to visit the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel where on April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated the night after he gave his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” address at the Mason Temple Church of God in Christ a few blocks away in support of the Sanitation Workers’ Strike.

In high school and college, I became more and more interested in Dr. King and his life’s work, so it was a spiritual experience to be looking up at this second-story balcony, especially on such a beautiful day nearly 50 years after he was killed.

One of the parts from his Mountaintop Speech stands out to me so starkly in today’s America. While sharing the Biblical story of the Good Samaritan, Dr. King says:

“But then the Good Samaritan came by, and he reversed the question: "If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?" That's the question before you tonight. Not, "If I stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to my job?" Not, "If I stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to all of the hours that I usually spend in my office every day and every week as a pastor?" The question is not, "If I stop to help this man in need, what will happen to me?" The question is, "If I do not stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to them?" That's the question.

Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us stand with a greater determination. And let us move on in these powerful days, these days of challenge, to make America what it ought to be. We have an opportunity to make America a better nation.”

There is no such thing as “Make America Great Again” because it has never been great for all its people. We should never want to go back to any time in our history. Instead, Dr. King states that we have an opportunity to make America a BETTER nation and one we need to continue to strive to make it what it OUGHT TO BE. Fifty years later we’ve made progress, but there’s still much more work yet to be done. And it’s on each and every one of us to make American what it ought to be.

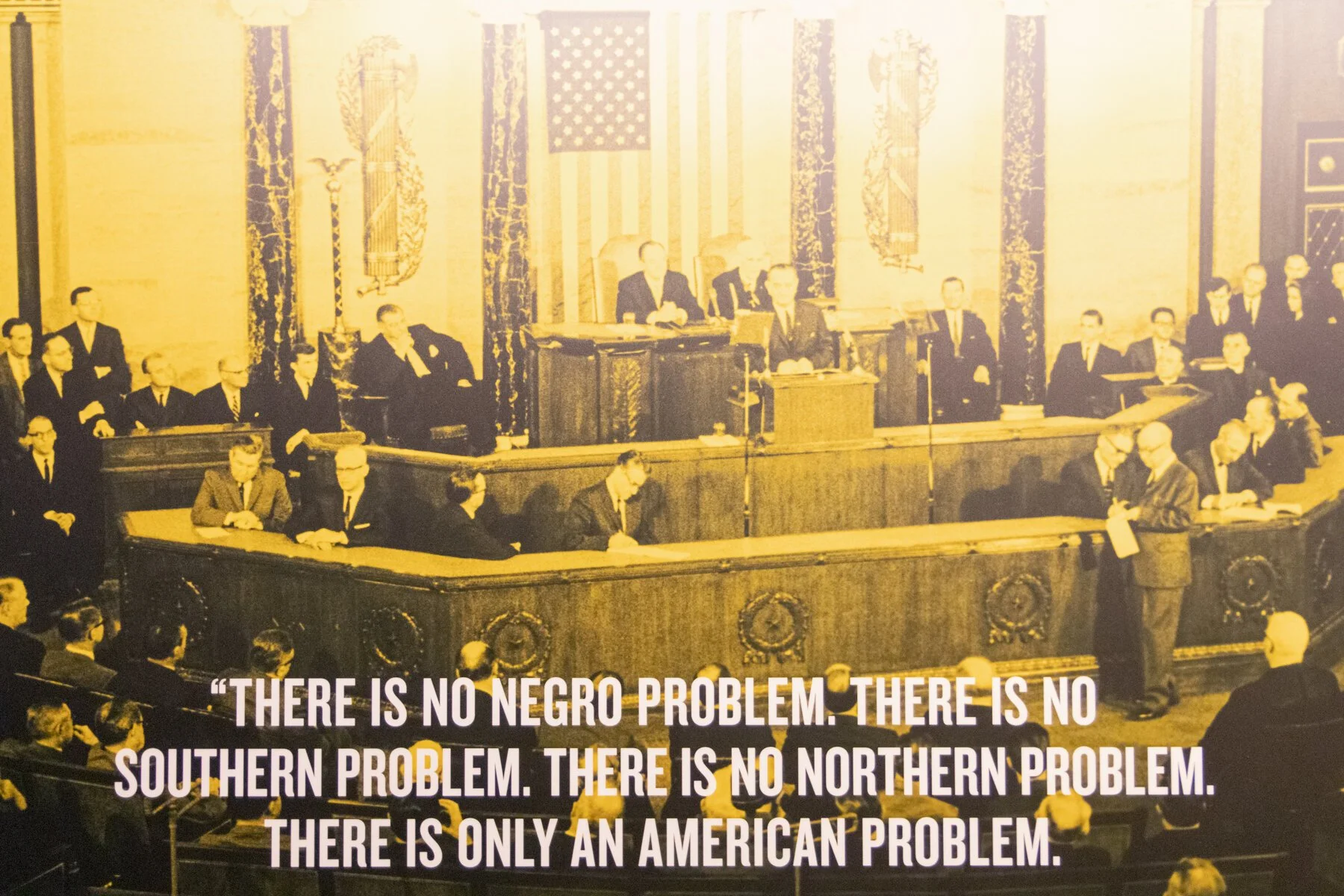

Upon entering the Civil Rights Museum, we were transported into the early history of the United States, beginning with the exhibit “A Culture of Resistance” of slavery in America from 1619 through 1861. The museum then progresses to “The Rise of Jim Crow” era of post-Civil War, and the “Separate is Not Equal” battles against segregation in the early and mid-20th century.

We then stepped into the heart of the civil rights era and walked onto the bus where Rosa Parks sat and sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott and “The Year They Walked” in 1955-1956 that brought out a young Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. into a nationwide movement.

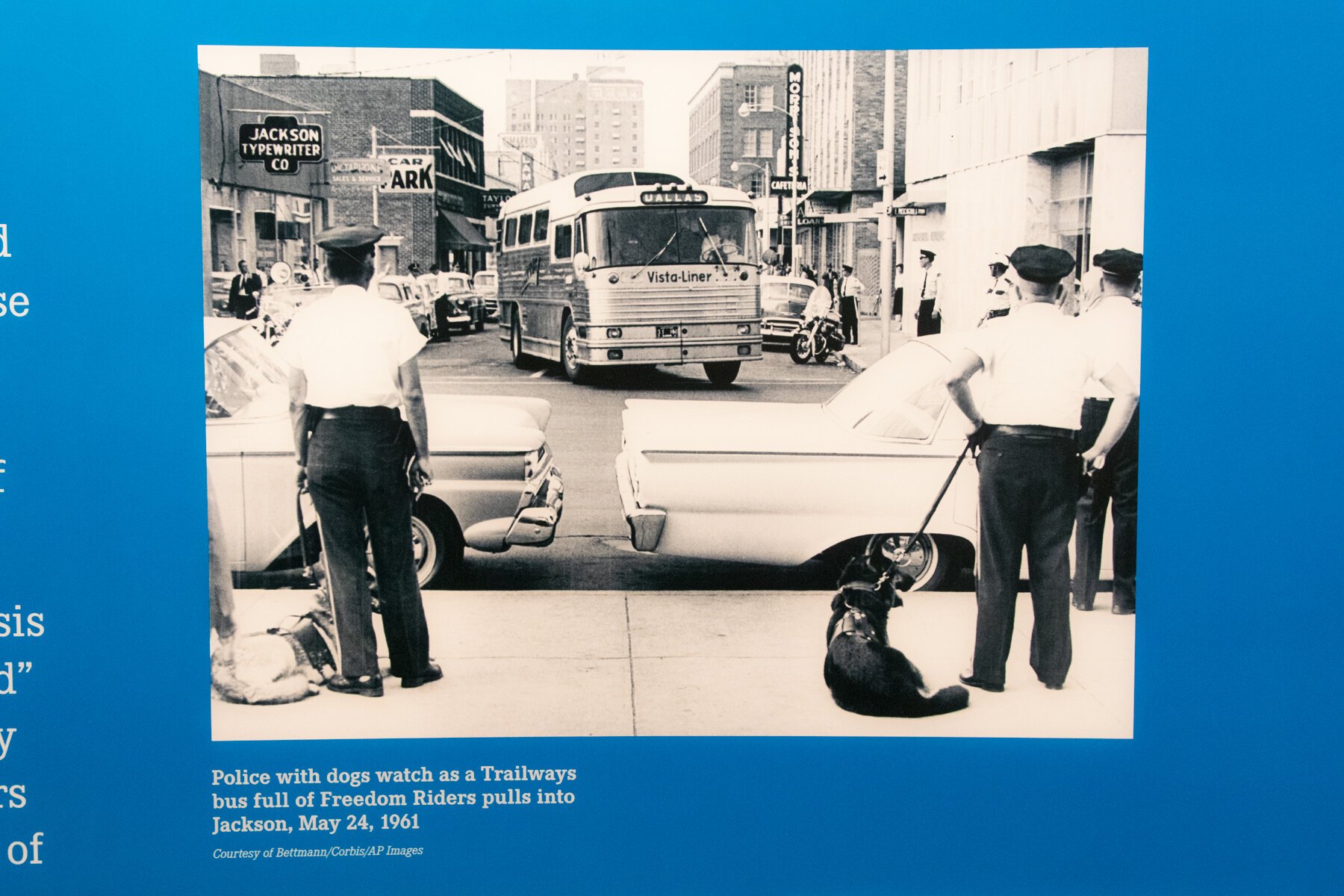

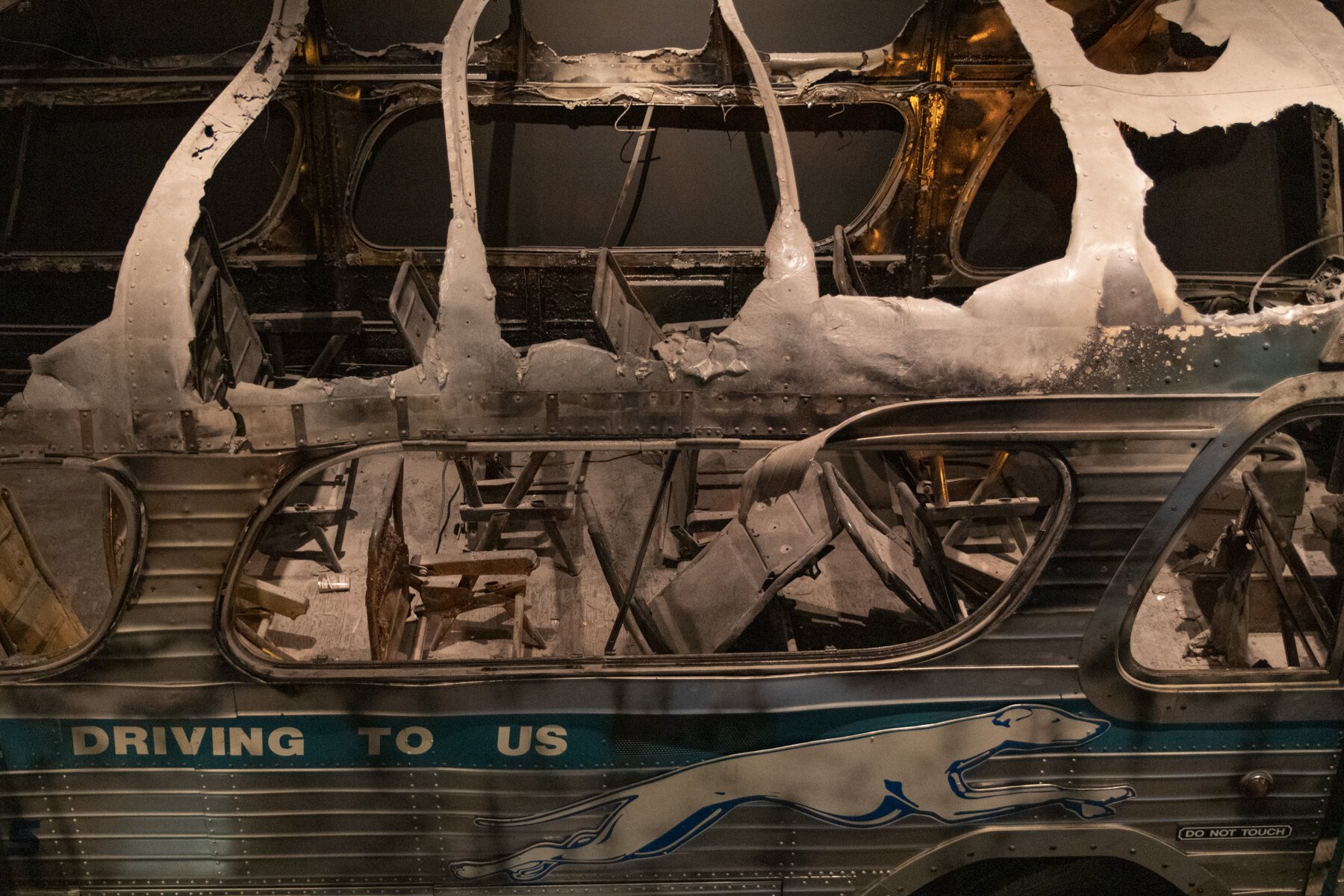

We continued down the timeline of the “Standing Up by Sitting Down” 1960 student sit-ins, and then to the horrifying “We Are Prepared to Die.” Following a 1960 Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation in bus and train terminals, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) initiated the Freedom Ride in 1961 that the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee began sending hundreds of young people both white and black into the south to challenge segregation on interstate buses and bus terminals.

On May 4, 1961, the freedom riders left Washington D.C. on two buses en route to New Orleans, Louisiana. On May 14, 1961, the Greyhound bus arrived in Anniston, Alabama where they were met by a mob of KKK members. They slashed the tires and followed the bus a few miles out of town where they fire-bombed it and then beat the riders as they tried to flee the flames. The other Trailways bus traveled to Birmingham, Alabama where those riders, which included civil rights activist and future U.S. Congressman from Georgia John Lewis, were also beaten by an angry white mob with metal pipes.

On May 24, 27 Freedom Riders were arrested for trying to use a “Whites Only” restroom in Jackson, Mississippi. They were sentenced and sent to the notorious Mississippi State Penitentiary Parchman Prison. Yet, more and more Freedom Rides continued to take place, often ending in Jackson where they were arrested. In total, more than 300 Freedom Riders were arrested, many of them sent to Parchman where they continued their protests from within their overcrowded cells.

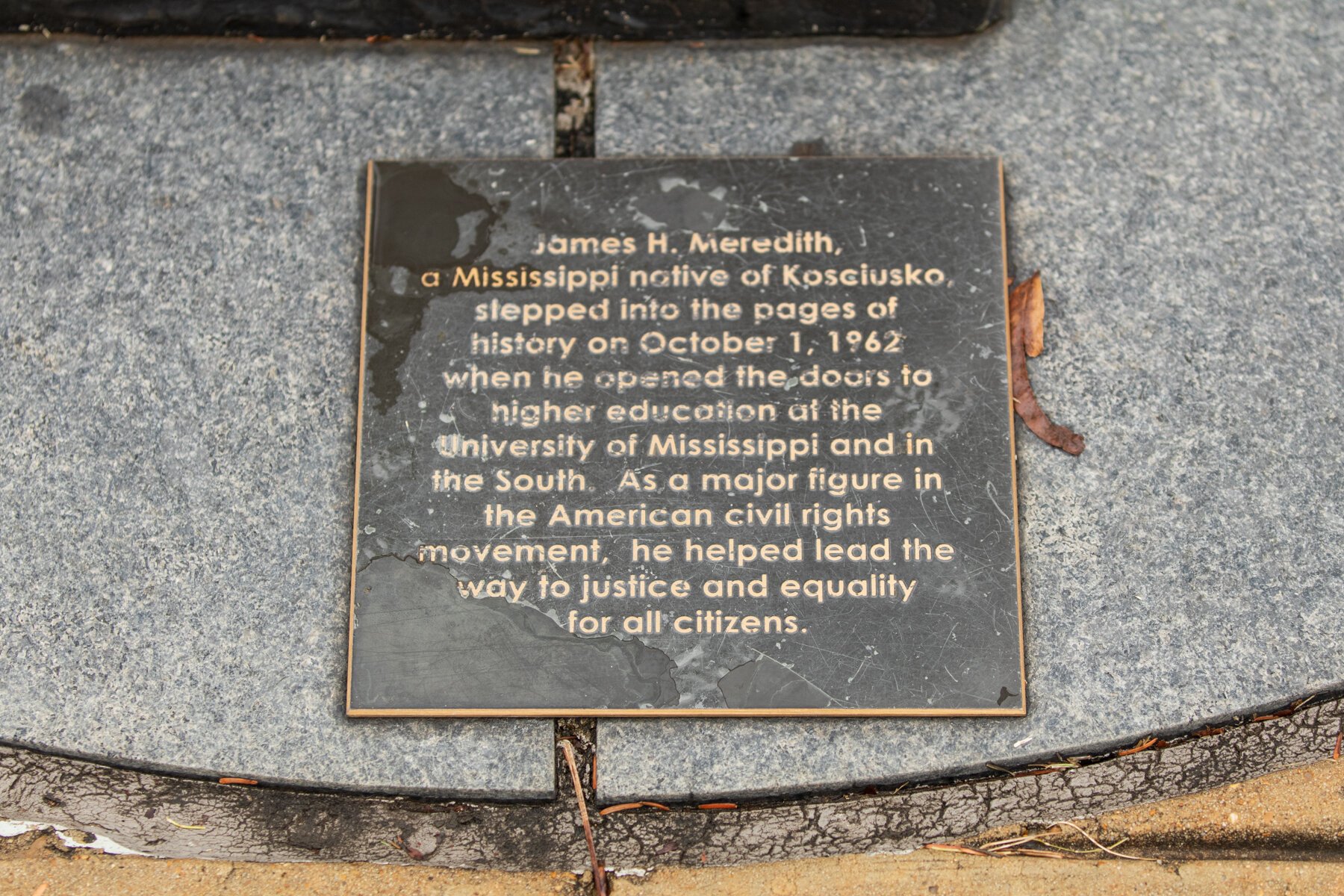

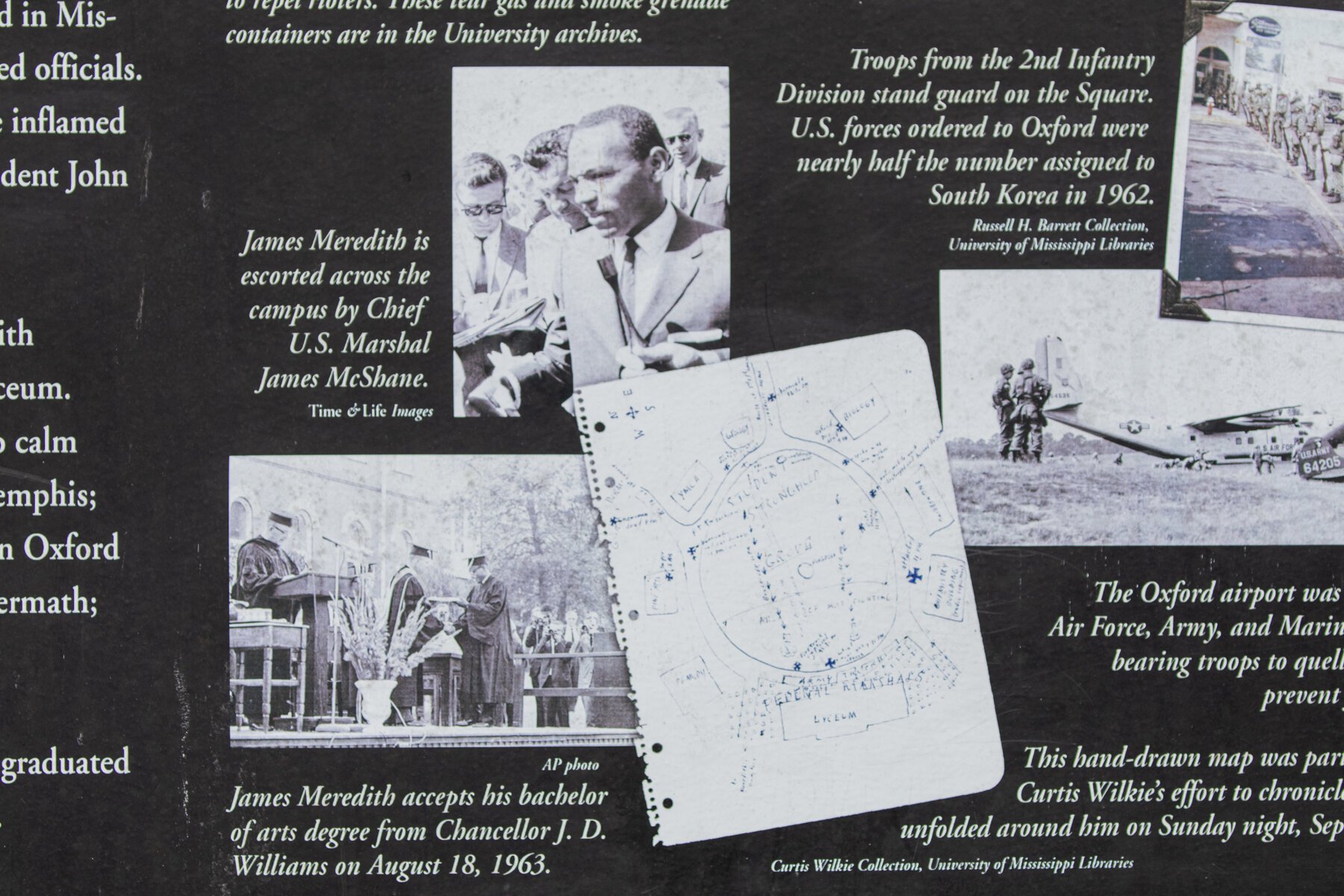

Around this time in 1961, after serving 9 years in the U.S. Navy, Mississippi native James Meredith applied to attend the all-white school of the University of Mississippi. Initially, he was accepted, but his admission was later withdrawn once the registrar discovered he was black. When Meredith arrived the following Fall at the university, the entrance was blocked.

Rioting soon erupted, and Attorney General Robert Kennedy sent 500 U.S. Marshals to the scene. Additionally, President John F. Kennedy sent military police and troops from the Mississippi National Guard and officials from the U.S. Border Patrol to keep the peace.

But on October 1, 1962, James Meredith became the first black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi, which is where our STATE 36: MISSISSIPPI project took place — more on that later.

As we continued our walk through the Civil Rights timeline, we made it to 1963 when Dr. King wrote the letter from the Birmingham City Jail, which you can read or listen to it from the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford. This letter called out inaction from much of white America, especially those of faith, to the strategies and actions of their nonviolent protests against racism. Within this letter, King wrote: “Justice too long delayed is justice denied,” and “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

In one part of his letter, Dr. King wrote in response to the published article by eight white Alabama clergymen against Dr. King’s methods and urgency of protest:

“The Negro has many pent-up resentments and latent frustrations. He has to get them out. So let him march sometime; let him have his prayer pilgrimages to the city hall; understand why he must have sit-ins and freedom rides. If his repressed emotions on not come out in these nonviolent ways, they will come out in ominous expressions of violence. This is not a threat; it is a fact of history. So I have not said to my people “get rid of your discontent.” But I have tried to say that this normal and healthy discontent can be channelized through the creative outlet of nonviolent direct action. Now, this approach is being dismissed as extremist. I must admit that I was initially disappointed in being so categorized.

But as I continue to think about the matter, I gradually gained a bit of satisfaction from being considered an extremist. Was not Jesus an extremist in love —- “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, pray for them that despitefully use you.” Was not Amos an extremist for justice… Paul an extremist for the gospel of Jesus Christ… Martin Luther an extremist… John Bunyan an extremist… Abraham Lincoln an extremist… Thomas Jefferson an extremist…

So the question is not whether we will be extremist, but what kind of extremist will we be. Will we be extremists for hate or will we be extremists for love?”

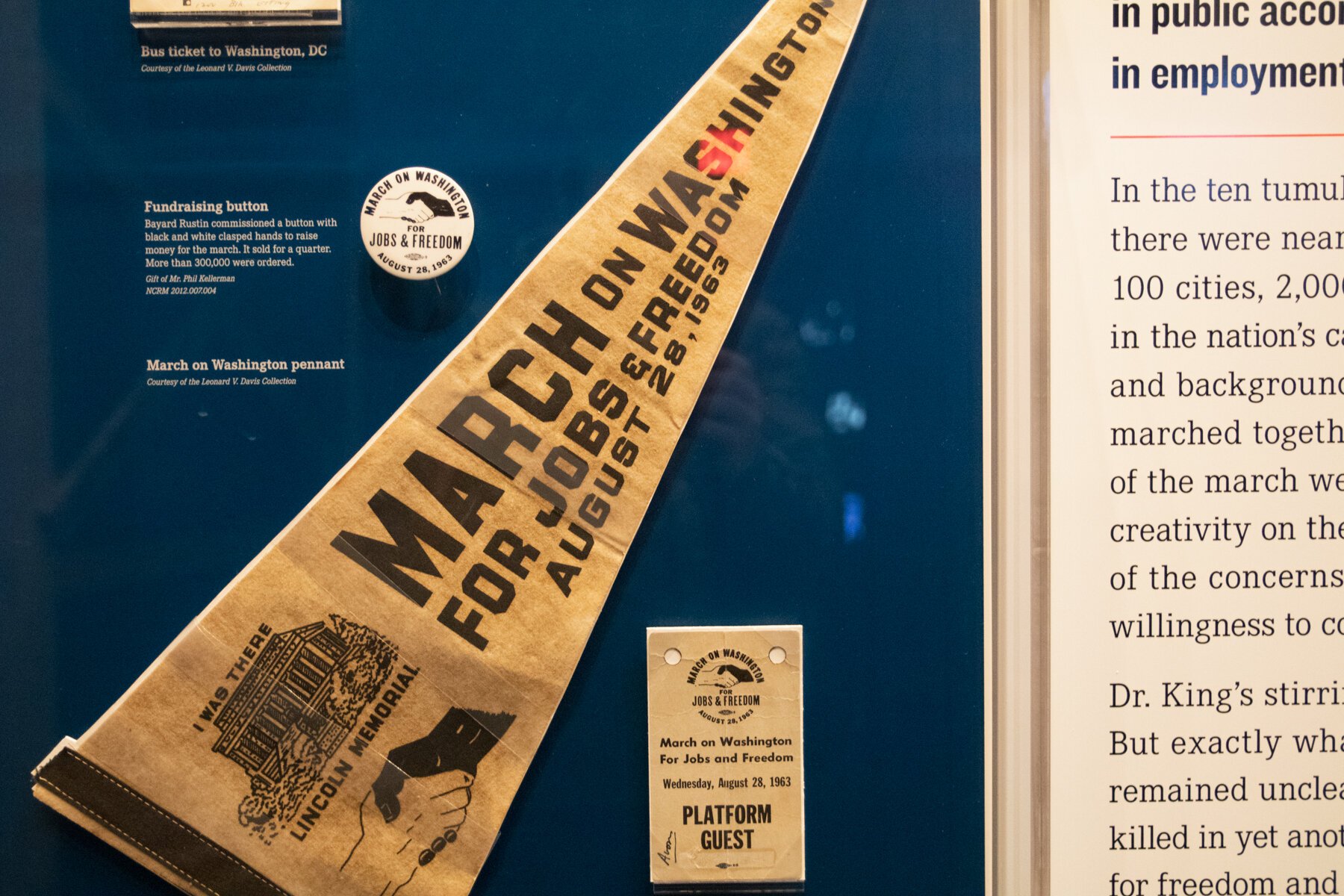

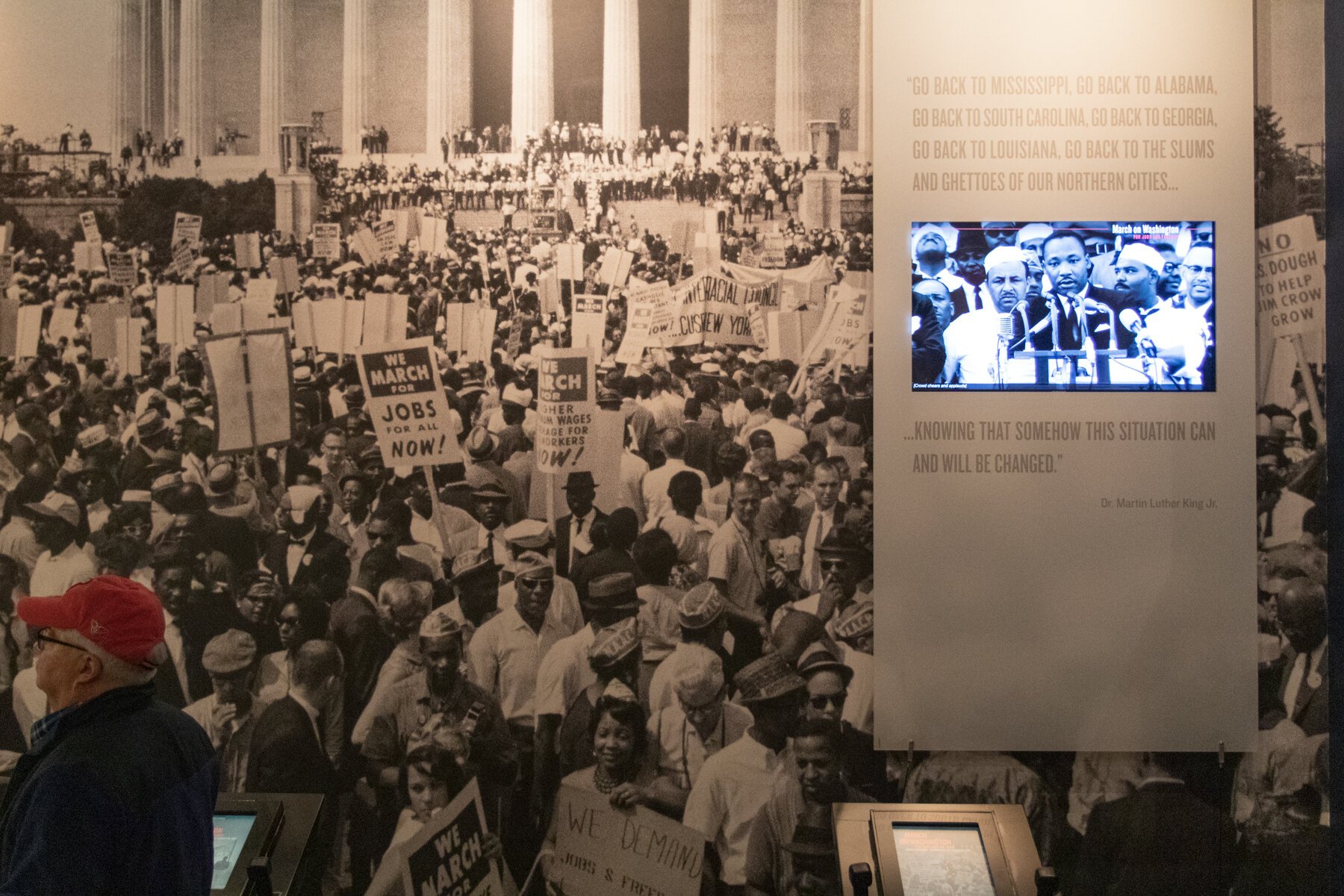

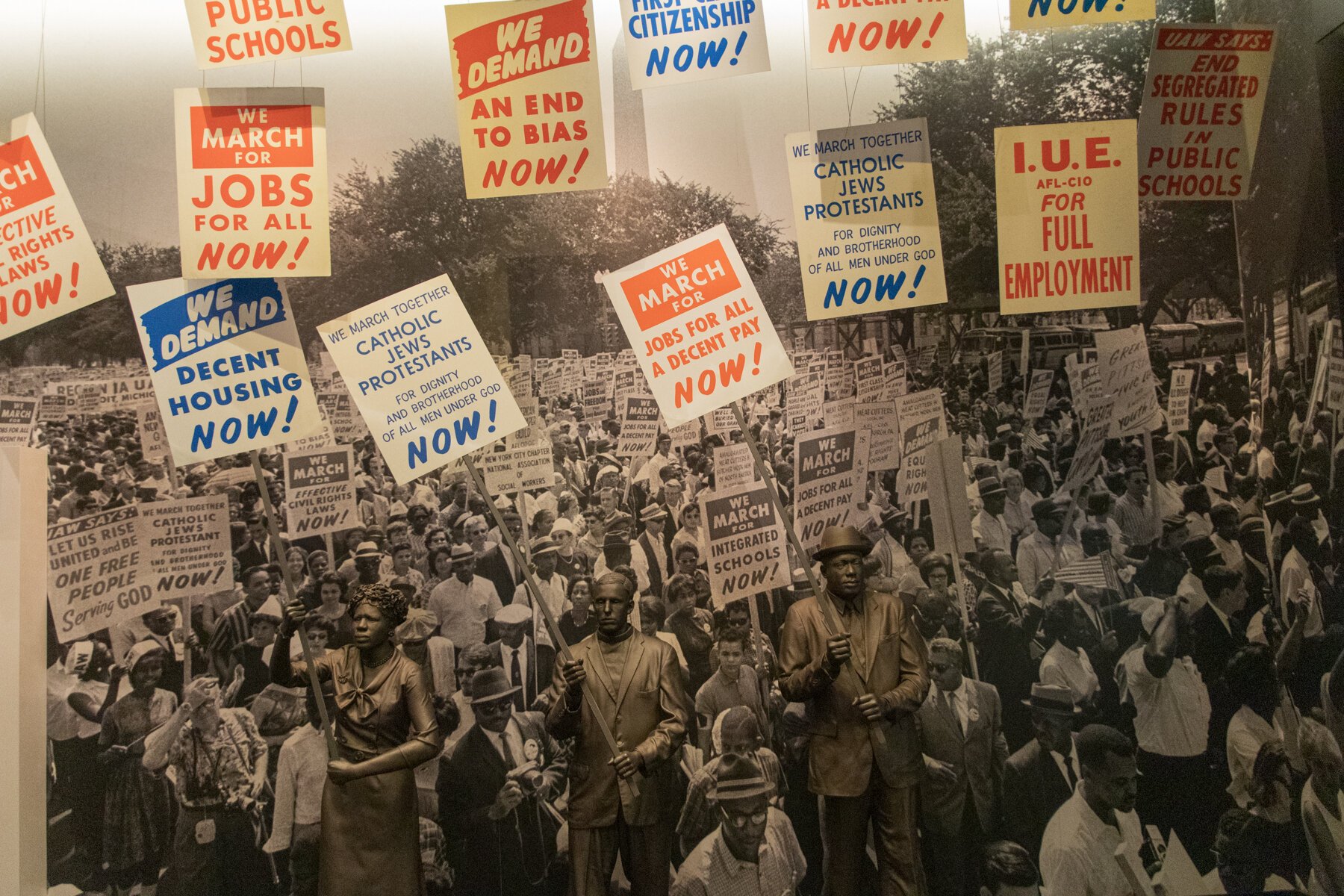

The next major Civil Rights milestone was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. This, of course, was where Dr. King stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in front of over 250,000 people and gave his “I Have a Dream” speech that spoke to households across the country and world and would (much later) become known as the greatest American speech in the 20th Century by a poll of scholars in 1999.

The March on Washington and the following year’s Freedom Summer (also known as the Mississippi Summer Project) are both major reasons for helping pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin and prohibits unequal application of voter registration requirements, and racial segregation in schools, employment, and public accommodations.

Despite the passing of the Civil Rights Act and Dr. King winning the Nobel Peace Prize that same year in 1964, voting rights and their activists were still being severely oppressed and abused. On February 18, 1965, 26-year-old African-American protester Jimmy Lee Jackson was shot by an Alabama state trooper while trying to protect his mother and died eight days later. Weeks later on March 7, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC) planned to take their cause directly to Alabama Governor George Wallace on a 54-mile march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital in Montgomery.

Led by Hosea Williams from the SCLC and now 25-year-old John Lewis from the SNCC, their march was stopped in its tracks by Alabama state police with whips, nightsticks, and tear gas who rushed the group just as they crossed the Edmund Pettis Bridge, forcefully beating them back to cross the river to Selma. This brutal scene became known as “Bloody Sunday” and was captured on national television, enraging many Americans and drawing civil rights and religious leaders of all faiths to Selma in protest, including Dr. King.

Then in 1968, Dr. King traveled to Memphis to give his support to the Sanitation Strike and poor working conditions of the city’s black workforce. In his speech the night before it happened, Dr. King said, “We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through” (King, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” 217). He believed the struggle in Memphis represented and exposed the greater need for economic equality and social justice across the country.

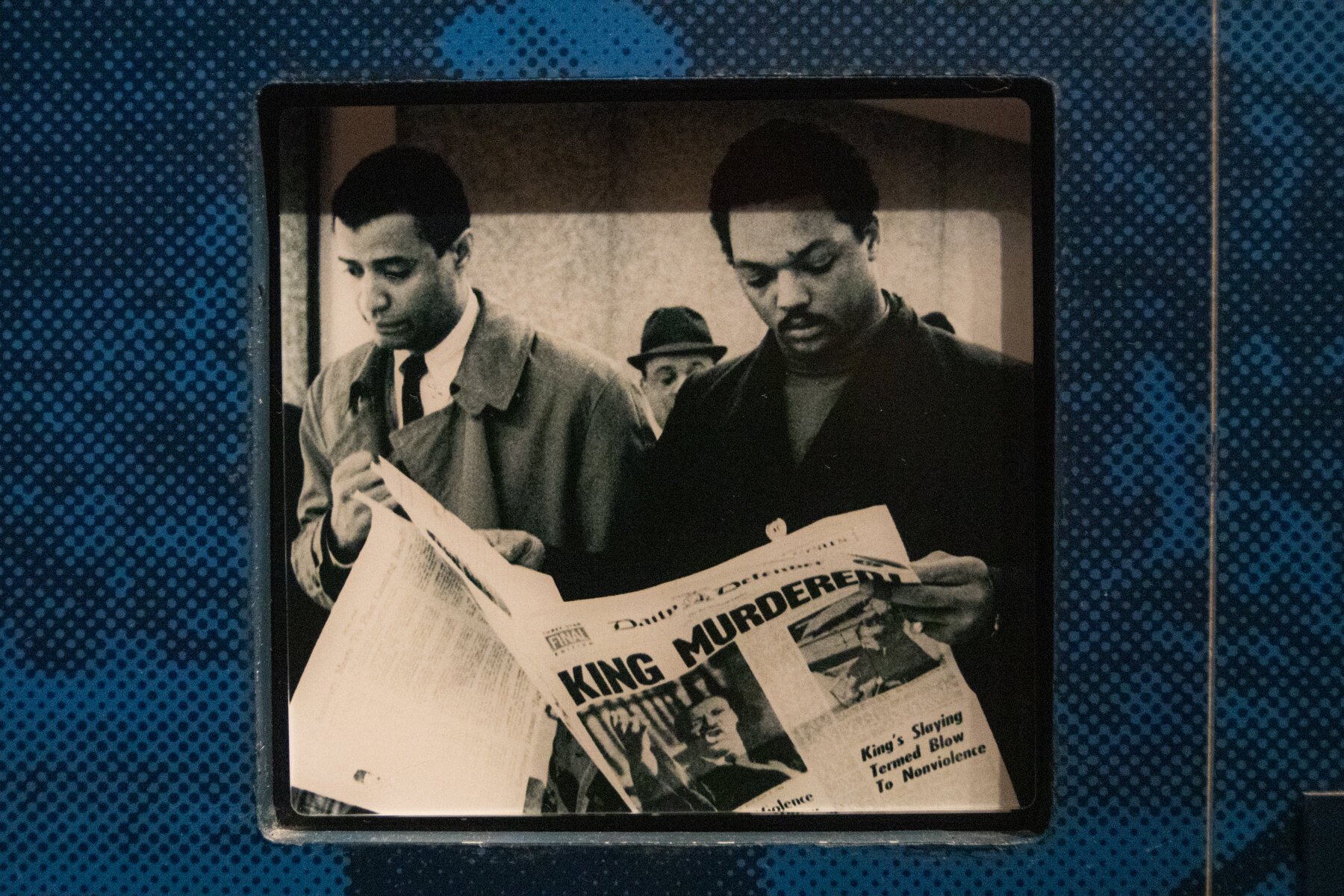

Then, it happened. On the balcony in front of Room 306 at the Lorraine Motel sometime after 6 PM as he was preparing to leave for dinner on Thursday, April 4, 1968. LIFE Magazine photographer Henry Groskinsky and writer Mike Silva arrived shortly after news broke and captured the somber scene in, “The Night MLK Was Murdered: A Photographer’s Story.”

“We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop … And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the promised land.”

— DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR.

After spending hours taking in all we could at the National Civil Rights Museum, it was closing time, and we had to leave. It’s still hard to form words to describe how we felt after experiencing this portion of our country’s history. I think if Obama were still the President, we would feel more optimistic in today’s America, but since the 2018 election, it seems any progress that has been made was quickly exterminated, reversed, undermined, dismantled, and disgraced.

The only thing those MAGA hats have done has exposed the hidden racism throughout the country. With a firm belief that everything happens for a reason, our hope is that by being exposed, we can have a better look at ourselves in the mirror as a country. We have made progress in the 50+ years since Dr. King, but we have so much further yet to go.

After our four-night stay along the Mississippi River, we drove further into Mississippi to Oxford for our STATE 36: MISSISSIPPI project to be held at the University of Mississippi, or better know to most as Ole Miss.

Our designer Tyler Barnes was an Assistant Professor of Graphic Design at Ole Miss, and since it happened to be the end of the semester and Christmas break, we had the campus and art building to ourselves. As we walked around campus, we found the James Meredith statue in the middle of the campus in the Lyceum.

As we saw in the National Civil Rights Museum, Meredith became the first African-American student admitted to the segregated University of Mississippi. It was one thing to read about it in the museum, it’s another thing to walk the sidewalks and into the buildings where he was the first person of color to sit in its classrooms.

Years later in 1966, Meredith’s pursuit for equality led him to plan a solo 220-mile March Against Fear from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi to highlight the continuing racism in the South and to encourage voter registration in black communities. On the second day of his march, Meredith was shot and wounded by a white sniper hiding in the bushes along his route. Major civil rights organizations continued his march on his behalf. Soon the march grew to over 15,000 participants who marched into the Mississippi state capitol city of Jackson — making it the largest civil rights march in state history.

While we know Mississippi today is much more than its historic role in the civil rights movement, it was hard for us not think about or even feel it everywhere we went because we were in it and surrounded by it. It’s on us, all of us, to ensure history doesn’t repeat itself.